Analysing The Spectral Biases in Generative Models

Diffusion and GAN models have demonstrated remarkable success in synthesizing high-quality images propelling them into various real-life applications across different domains. However, it has been observed that they exhibit spectral biases that impact their ability to generate certain frequencies and makes it possible to distinguish real images from fake ones. In this blog we analyze these models and attempt to explain the reason behind these biases.

Viewing Images in Frequency Domain

While we typically view images in the spatial domain—where every pixel directly represents brightness or color—another compelling perspective is to examine them in the frequency domain. By applying the 2D Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT)

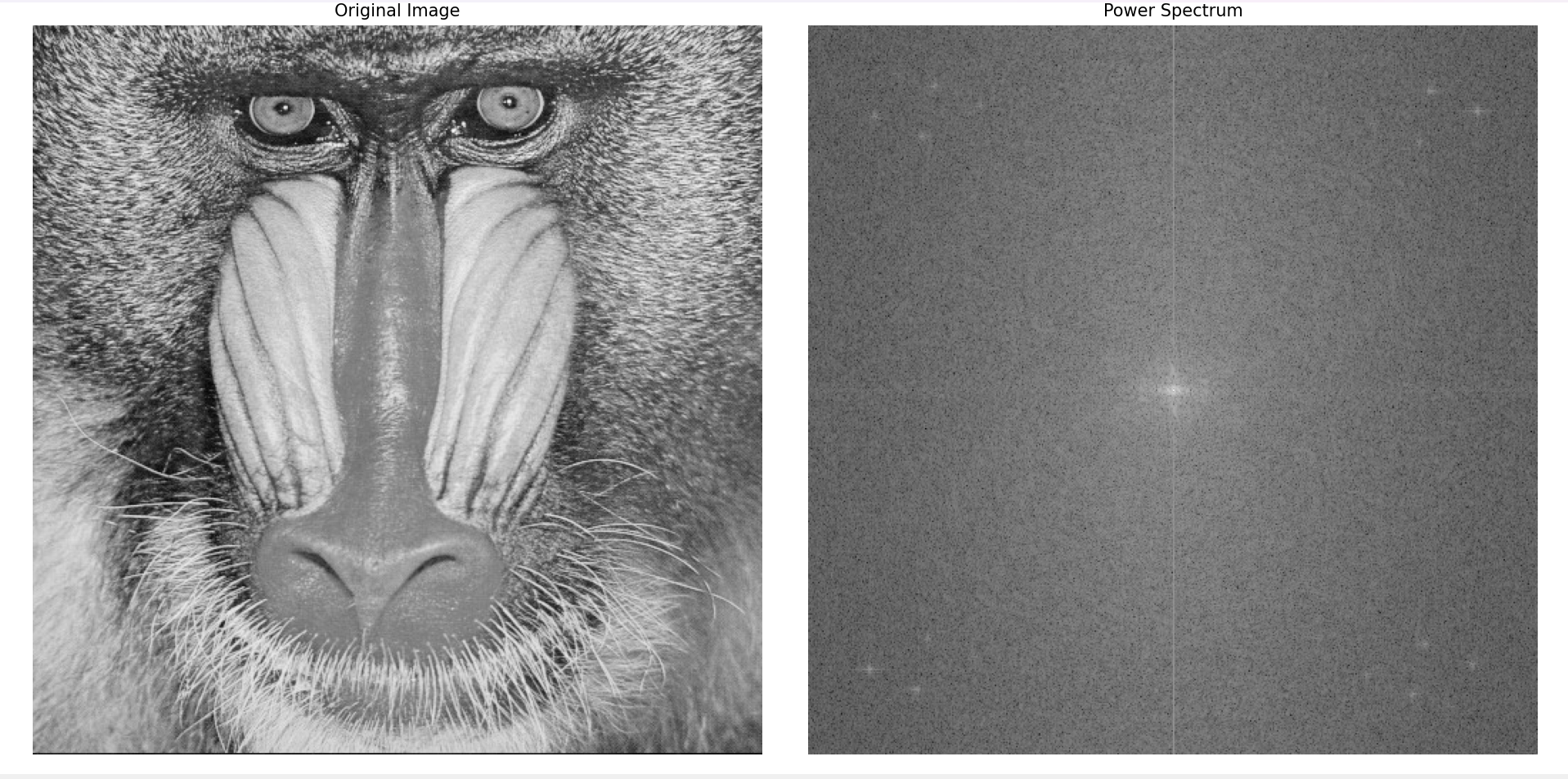

Here, $k=0,1,2…H-1$ and $l=0,1,2,…W-1$. So it outputs an image in the frequency domain of size ${H \times W}$. Here $\hat{I}[k, l]$ is a complex value at the pixel $I[x, y]$. For example, given below is a grayscale image of a baboon

To enhance power spectrum visualization, we remove the DC component, apply a Hann window

Frequency basically refers to the rate of change of colour in an imgae. The smooth regions (where colour or pixel intensities don’t change much) in an image correspond to low frequency while the regions containing edges and granular features (where colour changes rapidly) like hair, wrinkles etc correspond to high frequency. We can understand this by relating it to fitting 1D step functions using fourier series. The region of the step has large coefficients for the higher frequency waves while the other region has large coefficients for the low frequency waves.

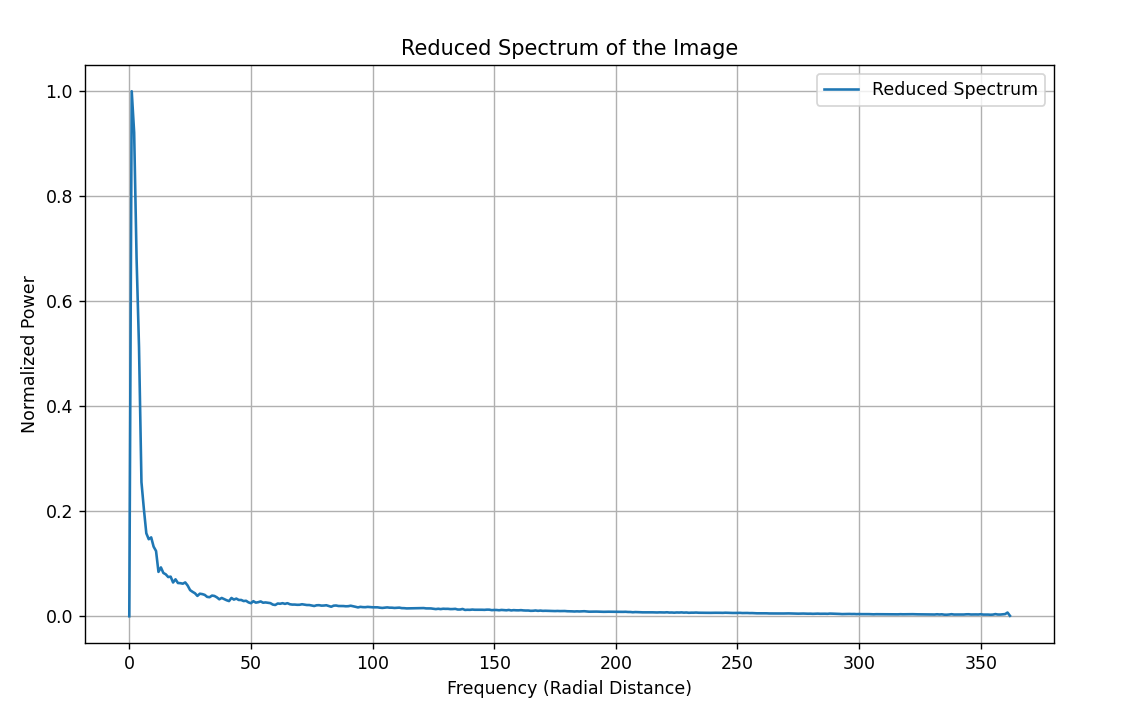

To analyse the frequency content, we estimate the Power Spectral Density (PSD) by squaring the magnitudes of the Fourier components. To visualise the spectrum as a 1D plot, the reduced spectrum S i.e. the azimuthal average over the spectrum in normalized polar coordinates $r \in [0, 1]$, $\theta \in [0, 2\pi)$ is calculated as

For the above image of baboon in frequency domain, the reduced spectrum is shown:

The power spectrum of natural images follows a power law i.e. $\frac{1}{f^\alpha}$ with $\alpha$ ~ 2. A more complete model of the mean power spectra (using polar coordinates) can be written as

\[E[|I(f, \theta)|^2] = \frac{A_s(\theta)}{f^{\alpha_s(\theta)}}\]in which the shape of the spectra is a function of orientation. The function $A_s(\theta)$ is an amplitude scaling factor for each orientation and $\alpha_s(\theta)$ is the frequency exponent as a function of orientation. Both factors contribute to the shape of the power spectra

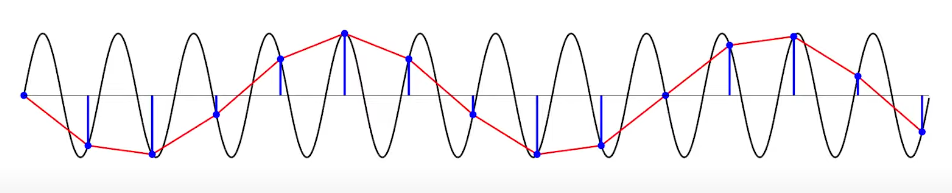

In digital imaging, understanding aliasing and the Nyquist Frequency is crucial for accurately capturing and representing details. When we convert a continuous scene, like a real world view into a digital image, we sample it at discrete intervals i.e. each pixel acts as a tiny snapshot of the scene at that point. The Nyquist Frequency, defined as half of the sampling rate, is the highest spatial frequency that can be accurately captured by this pixel grid. Let us see why. Imagine a 1D wave. To represent its frequency accurately, we need at least two samples per cycle: one to capture the crest (peak) and one to capture the trough. Since images are discretized in space, the maximum frequency is determined by the Nyquist frequency. For a square image, $H = W$, it is given by $f_{\text{nyq}} = \sqrt{k^2 + l^2} = \frac{H}{\sqrt{2}}$, i.e. for $r = 1$.

If the details in the scene change more rapidly than this (i.e., they have a higher spatial frequency than the Nyquist limit), we will be unable to capture the shape of the actual wave and this high frequency oscillating region will be considered as a smooth low frequency region. Thus, when the pixel grid cannot capture both the crest and trough, or the rapid change of light intensity, this leads to a phenonmenon called aliasing. Aliasing causes high-frequency details to appear as misleading lower-frequency patterns or distortions, like the moiré effect

Analysis of Bias in GANs

Now, let us analyze spectral biases

This was earlier attributed to a mere scarcity of high frequencies in natural images, but recent works

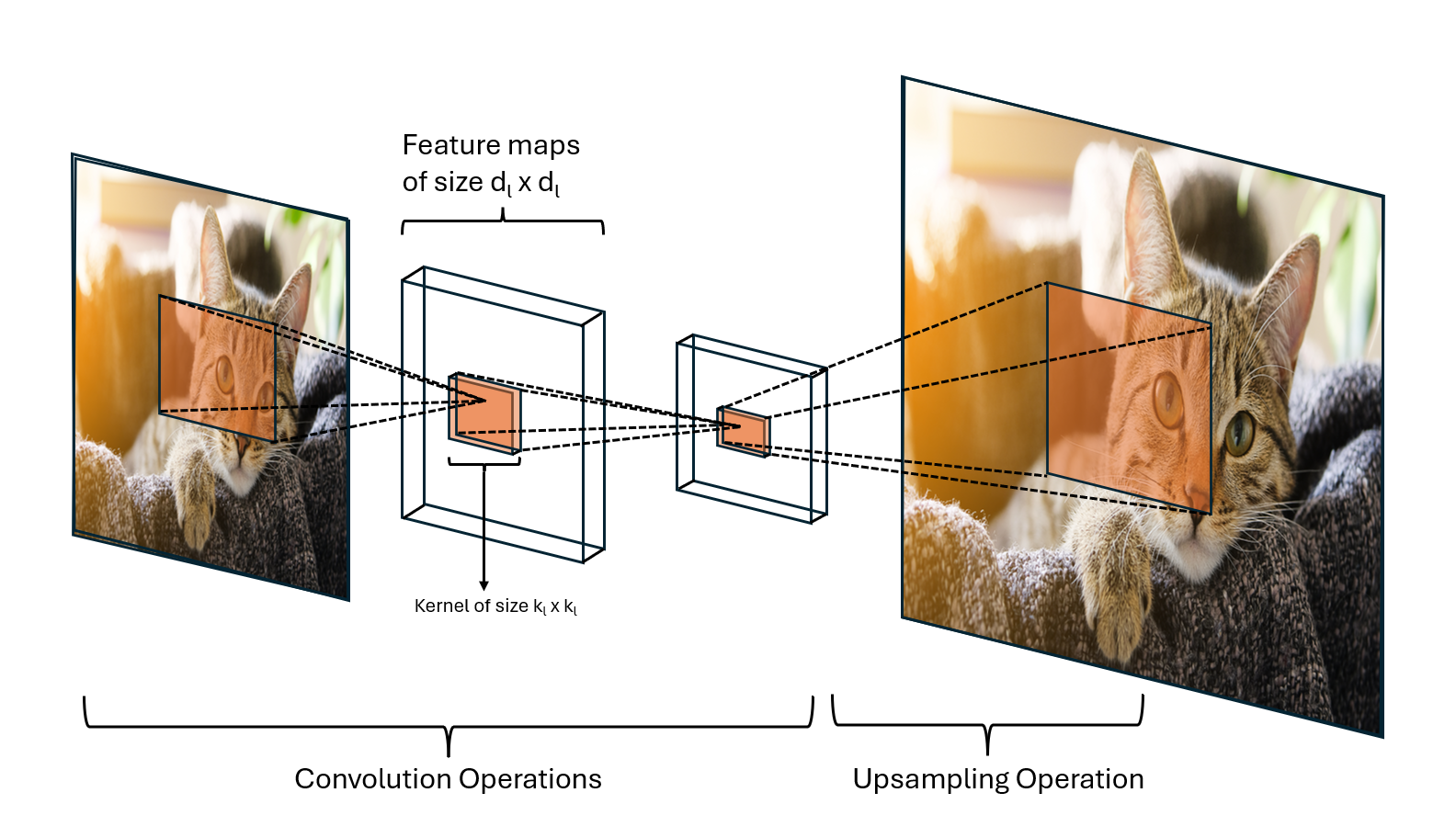

Setting Up the Generative CNN Structure

We’ll start by setting up the structure of a generative CNN model, which typically consists of a series of convolutional layers with filters that learn different features. Our CNN is structured as a stack of convolutional layers, with each layer represented as:

where:

- $\text{H}_l$ : The feature map at layer l.

- $F_{l}^{i,c}$: A convolutional filter at layer l, of size ${k_l} \times \text{k}_l$ , that connects input channel c to output channel i.

- $\text{Up}(\cdot)$ : The upsampling operator, which increases the spatial dimensions, helping generate higher-resolution outputs.

- $\sigma(\cdot)$: A non-linearity function, typically a ReLU.

Inputs: The initial feature map is represented by $H_1$ with shape $d_0$ $\times$ $d_0$ .

Parameters: The model parameters are $W$ (weights for each layer).

Layers: The network is built from convolutional layers, each generating new feature maps based on its input. Each layer also performs upsampling and non-linear transformations to increase resolution and control spatial frequencies.

Before starting with the analysis of a filter’s spectrum, we first need to introduce the idea of viewing ReLU as a fixed binary mask. Why do we need to do this? We’ll look at it in just a moment.

ReLU as a Fixed Binary Mask

Considering ReLUs to be the activation $\sigma(\cdot)$, they can then be viewed as fixed binary masks

This proof has been inspired from the paper “Spatial Frequency Bias in Convolutional Generative Adversarial Networks”

Mathematically, We are working with a scalar ouptut $\mathcal{f}(W)$ of a convolutional layer in a finite ReLU-CNN. Therefore, the function depends on the weight parameter W and the latent input $H_{1}$. Now, we need to show that for any neighbourhood around $W$, the output of the function is entirely non-negative or entirely non-positive. This means proving that the set of parameters where 𝑓 changes sign within every neighbourhood of 𝑊 (i.e., it crosses zero somewhere in every neighbourhood) has measure zero.

\[\implies G = \{ W \in \mathcal{W} \mid \forall \mathcal{N}(W), \exists U, V \in \mathcal{N}(W) : f(U) < 0 < f(V) \}\]where $\mathcal{N}(W)$ represents the neighbourhood of $W$. $G$ captures the parameter values $W$ where $f(W)$ crosses zero in every neighborhood. Therefore, our objective becomes to show that $G$ has measure zero.

A finite ReLU-CNN has a finite number of neurons and, hence, a finite number of ReLU activations. Each ReLU activation behaves like a piecewise linear function that “splits” the parameter space into regions.

$\implies$ For any fixed configuration of active/inactive neurons, $f(W)$ becomes a polynomial function of $W$. Thus, for each configuration of ReLU activations, $f(W)$ behaves as a polynomial, with each configuration yielding a different polynomial form.

A polynomial function on $\mathbb{R}^n \text{ to } \mathbb{R}$ has a measure zero set of zero-crossings in the parameter space

$\implies$ A finite set of such polynomials also has a measure zero set of zero-crossings. $\therefore$ $G$ is also a measure zero set.

Finally, this reasoning holds for any scalar output $f$ of the network, at any spatial location or layer. Given that there are only a finite number of such outputs in a finite network, the measure of $G$ for all outputs is still zero, thereby completing the proof.

To summarize, the proof hinges on the fact that with ReLU activations, each layer’s output depends on whether each neuron is active or inactive. For any fixed set of active/inactive states, the network’s output behaves as a polynomial with respect to the parameters. Since polynomials only have zero-crossings on a measure zero subset of the parameter space, the overall network exhibits non-negative or non-positive output behavior almost everywhere in the parameter space.

This implies that almost all regions of the parameter space are “stable” in terms of sign, and this stability is a result of the ReLU non-linearity creating a finite set of polynomial behaviors for 𝑓.

Why This Matters

The key consequences and takeaways of this result are:

Simplified Frequency Control: Since the ReLUs act like fixed binary masks, they don’t introduce additional variability. The network’s spectral characteristics become easier to analyze because the ReLUs don’t actively change the frequency content in these neighbourhoods.

Shifts Control to Filters: The network’s ability to adjust the output spectrum depends more on the convolutional filters ${F}_l^{i,c}$ than on the non-linear ReLUs.

Onto The Analysis of Filters

Now that we have set up the base, we can now move on analyzing the effect of convolutional filters on the spectrum.

The filters ${F}_l^{i,c}$ in each convolutional layer are the primary tools for shaping the output spectrum. Thus, the filters try to carve out the desired spectrum out of the input spectrum which is complicated by:

- Binary masks (ReLU) which although don’t create new frequencies, but distort what frequencies are passed onto the next layer.

- Aliasing from Upsampling.

Now, take any two spatial frequency components \(U =\mathcal{F}_{l}^{i,c}(u_0, v_0)\) and \(V = \mathcal{F}_{l}^{i,c}(u_1, v_1)\) on the kernel $F_l$ of the $l$’th convolution layer of spatial dimension $d_l$ and filter size $k_l$, at any point during training. Let $G_l$ be a filter of dimension \(\mathbb{R}^{d_l \times d_l}\). Because of it’s dimension, it is an unrestricted filter that can hypothetically model any spectrum in the output space of the layer. Hence, we can write $F_l$ as a restriction of $G_l$ using a pulse P of area $k_l^2$ :

\[F_l = P.G_l\] \[P(x,y) = \begin{cases} 1, & \text{if } 0 \leq x, y < k_l \\ 0, & \text{if } k_l \leq x,y \leq d_l \end{cases}\]Applying Convolution Theorem on $F_l$:

\[\mathcal{F}_l = \mathcal{F}_{P} \cdot \mathcal{G}_l = \mathcal{F}\{P\} * \mathcal{F}\{G_l\}\]where $\mathcal{F}(\cdot)$ represents the $d_l$ point DFT.

From (1), the Fourier Transform of $P(x,y)$ is given by:

\[\mathcal{F}\{P(x, y)\}(u, v) = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} P(x, y) e^{-i 2 \pi (u x + v y)} \, dx \, dy\] \[\quad \implies \mathcal{F}\{P(x, y)\}(u, v) = \int_0^{k_l} \int_0^{k_l} e^{-i 2 \pi (u x + v y)} \, dx \, dy \quad\]$\text{Evaluating wrt x:}$

\[\int_0^{k_l} e^{-i 2 \pi u x} d x=\frac{1-e^{-i 2 \pi u k_l}}{i 2 \pi u}=k_l \operatorname{sinc}\left(\frac{u k_l}{d_l}\right)\]$\text{Evaluating wrt y:}$

\[\int_0^{k_l} e^{-i 2 \pi v y} d y=\frac{1-e^{-i 2 \pi v k_l}}{i 2 \pi v}=k_l \operatorname{sinc}\left(\frac{v k_l}{d_l}\right)\]$\text{Combining these results, the Fourier transform of P(x,y) is:}$

\[\mathcal{F}\{P(x, y)\}(u, v)=k_l^2 \operatorname{sinc}\left(\frac{u \kappa_l}{d_l}\right) \operatorname{sinc}\left(\frac{v k_l}{d_l}\right)\]When the function is sampled, aliasing causes the spectrum to repeat periodically in the frequency domain. Each repetition of the sinc function at integer multiples of the sampling frequency creates a periodic aliasing pattern. In case of P(x,y) the function transforms into:

\[\operatorname{Sinc}(u, v)=\frac{\sin \left(\frac{\pi u k_l}{d_l}\right) \sin \left(\frac{\pi v k_l}{d_l}\right)}{\sin \left(\frac{\pi u}{d_l}\right) \sin \left(\frac{\pi v}{d_l}\right)} e^{-j \pi(u+v)\left(\frac{k_{l}-1}{d_l}\right)}\]Here’s a breakdown of the components:

$\sin(\frac{\pi u k_l}{d_l})$ : This is the sinc function scaled by the ratio of $k_l$ and $d_l$, which determines how the spatial box function in the spatial domain transforms in the frequency domain.

The phase term $e^{-j \pi(u+v)\left(\frac{k_{l}-1}{d_l}\right)}$ : This accounts for a shift in the frequency domain. This phase shift arises due to the position of the box function in the spatial domain. This ensures that the Fourier transform reflects the correct location of the box function.

Calculating for the correlation between $U$ and $V$:

\[\operatorname{Cov}[U, V]=\operatorname{Cov}\left[\operatorname{Sinc} * \mathcal{F}\left\{G_l\right\}\left(u_0, v_0\right), \operatorname{Sinc} * \mathcal{F}\left\{G_l\right\}\left(u_1, v_1\right)\right]\]To expand this covariance term, we express $U$ and $V$ in terms of the sinc function and the frequency components of $G_l$:

\[\begin{aligned} U & =\sum_{u, v} \operatorname{Sinc}(u, v) \cdot \mathcal{F}\left\{G_l\right\}\left(u_0-u, v_0-v\right) \\ V & =\sum_{\hat{u}, \hat{v}} \operatorname{Sinc}(\hat{u}, \hat{v}) \cdot \mathcal{F}\left\{G_l\right\}\left(u_1-\hat{u}, v_1-\hat{v}\right) \end{aligned}\] \[\implies \operatorname{Cov}[U, V]=\operatorname{Cov}\left(\sum_{u, v} \operatorname{Sinc}(u, v) \cdot \mathcal{F}\left\{G_l\right\}\left(u_0-u, v_0-v\right), \sum_{\hat{u}, \hat{v}} \operatorname{Sinc}(\hat{u}, \hat{v}) \cdot \mathcal{F}\left\{G_l\right\}\left(u_1-\hat{u}, v_1-\hat{v}\right)\right)\]This expands to: \(\operatorname{Cov}[U, V]=\sum_{u, v} \sum_{\hat{u}, \hat{v}} \operatorname{Sinc}(u, v) \operatorname{Sinc}^*(\hat{u}, \hat{v}) \cdot \operatorname{Cov}\left(\mathcal{F}\left\{G_l\right\}\left(u_0-u, v_0-v\right), \mathcal{F}\left\{G_l\right\}\left(u_1-\hat{u}, v_1-\hat{v}\right)\right)\)

Since $G_l$ is assumed to have independent frequency components (with variance $\sigma^2$ for each component), the covariance between any two distinct components is zero, while the variance of each component is $\sigma^2$. Therefore, the covariance term simplifies because we only need to consider the terms where $(u,v) = (\hat{u},\hat{v})$:

\[\operatorname{Cov}[U, V]=\sum_{u, v} \operatorname{Sinc}(u, v) \operatorname{Sinc}\left(u_0-u_1-u, v_0-v_1-v\right) \cdot \sigma^2\]The final covariance expression simplifies further by factoring out $\sigma^2$ and recognizing the sum as a convolution:

\[\operatorname{Cov}[U, V]=\sigma^2 \sum_{u, v} \operatorname{Sinc}(u, v) \operatorname{Sinc}\left(u_0-u_1-u, v_0-v_1-v\right)\]Using the definition of convolution, we get:

\[\operatorname{Cov}[U, V]=\sigma^2 \cdot \operatorname{Sinc} * \operatorname{Sinc}\left(u_0-u_1, v_0-v_1\right)\]Since the sinc function is defined over the finite output space $d_l \times d_l$, the convolution integrates to $d_l^2$, giving us:

\[\operatorname{Cov}[U, V]=\sigma^2 d_l^2 \operatorname{Sinc}\left(u_0-u_1, v_0-v_1\right)\]Next, we calculate the variance of $U$ (or similarly for $V$, due to symmetry) using the expression for $U$ from earlier. This is computed as:

\[\operatorname{Var}[U]=\operatorname{Var}\left(\sum_{u, v} \operatorname{Sinc}(u, v) \cdot \mathcal{F}\left\{G_l\right\}\left(u_0-u, v_0-v\right)\right)\]Using independence again, the variance simplifies to:

\[\operatorname{Var}[U]=\sum_{u, v}|\operatorname{Sinc}(u, v)|^2 \cdot \operatorname{Var}\left(\mathcal{F}\left\{G_l\right\}\left(u_0-u, v_0-v\right)\right)\]Substituting the variance $\sigma^2$ of each independent component:

\[\operatorname{Var}[U]=\sigma^2 \sum_{u, v}|\operatorname{Sinc}(u, v)|^2\]The sum over \(|Sinc(u,v)|^2\) evaluates to \(d_l^2k_l^2\), so:

\[\operatorname{Var}[U]=\sigma^2 d_l^2 k_l^2\]Finally, we calculate the complex correlation coefficient between $U$ and $V$, which is defined as:

\[\operatorname{corr}(U, V)=\frac{\operatorname{Cov}[U, V]}{\sqrt{\operatorname{Var}[U] \operatorname{Var}[V]}}\]Substituting,

\[\operatorname{corr}(U, V)=\frac{\sigma^2 d_l^2 \operatorname{Sinc}\left(u_0-u_1, v_0-v_1\right)}{\sqrt{\sigma^2 d_l^2 k_l^2 \cdot \sigma^2 d_l^2 k_l^2}}\] \[\implies \operatorname{corr}(U, V)=\frac{\operatorname{Sinc}\left(u_0-u_1, v_0-v_1\right)}{k_l^2}\]Now, if the $U$ and $V$ frequencies are diagonally adjacent, then the correlation coefficient becomes:

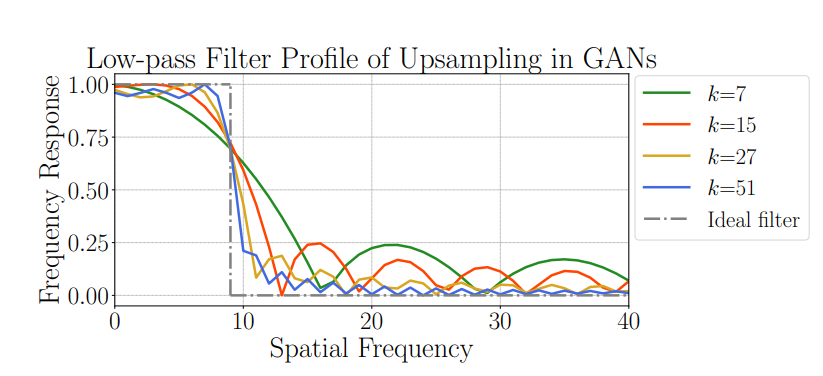

\[\begin{equation} |\operatorname{corr}(U, V)|=\frac{\sin ^2\left(\frac{\pi k_l}{d_l}\right)}{k_l^2 \sin ^2\left(\frac{\pi}{d_l}\right)} \end{equation}\]This result indicates that the correlation between two frequency components in the spectrum of $F_l$ is inversely related to the filter size $k_l$. A larger filter (i.e., higher $k_l$) reduces the correlation between frequencies, enhancing the filter’s ability to represent diverse frequencies independently. Conversely, a smaller filter (lower $k_l$) increases correlation, meaning that adjustments to one part of the frequency spectrum impact neighboring frequencies, thereby limiting the filter’s effective capacity to separate and individually adjust each frequency component.

In each convolutional layer, the maximum spatial frequency that can be achieved is bounded by the Nyquist frequency. This means that a convolutional layer can accurately control spatial frequencies within the range $[0, \frac{d_l}{2d}]$ without aliasing. As a result, the high-frequency components are predominantly generated by the earlier layers of the CNN, which have larger spatial dimensions $d_l$. With a fixed filter size $k_l$, an increase in $d_l$ leads to higher correlations across the filter’s spectrum, thereby reducing the filter’s effective capacity to fine-tune individual frequencies. Consequently, earlier layers, responsible for creating high frequencies, face more restrictions in their spectral capacity compared to later layers with smaller $d_l$, which have greater flexibility for spectral adjustments.

Moreover, while only the earlier layers can produce high frequencies without aliasing, all layers can contribute to the low-frequency spectrum without this restriction. Thus, the spatial extent of the effective filter acting on low frequencies is consistently larger than that acting on high frequencies. Even if larger filter sizes $k_l$ are used in the earlier layers to counterbalance the larger $d_l$ , low frequencies continue to benefit from a larger effective filter size compared to high frequencies, which ultimately results in lower correlation at low frequencies.

In addition to this, some works

Frequency bias in Diffusion Models

It has been well known that like GANs

Diffusion models

Let the input image that we want to reconstruct be $x_0$ and $\epsilon$ be white noise of variance 1. $x_t$ is the noised sample at time step t. Hence we can write

\[\mathbf{x}_t = \sqrt{\bar{\alpha}} \mathbf{x}_0 + \sqrt{1 - \bar{\alpha}} \epsilon\]In the denoising process , let $h_t$ be the filter that is learned . So $h_t^* $ is the optimal filter which minimizes the loss function of the diffusion model

Now if the optimal filter $\mathbf{h}_t$ is learned, then we approximate $\epsilon$ by $\mathbf{h}_t * \mathbf{x}_t$ so our noising step equation becomes:

\[x_t = \sqrt{\bar{\alpha}} \, x_0 + \sqrt{1 - \bar{\alpha}} \, (h_t * x_t)\]Taking the DFT on both sides, we get

\[X_t = \sqrt{\bar{\alpha}} \, X_0 + \sqrt{1 - \bar{\alpha}} \, (H_t\times X_t)\]Rearranging the equation, we get

\[\left( \frac{1 - \sqrt{1 - \bar{\alpha}}}{\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}}} H_t \right) X_t = X_0\]Let $\left( \frac{1 - \sqrt{1 - \bar{\alpha}}}{\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}}} H_t \right)$ = $G_t$. Here $G_t$ is the frequency response of a filter $g_t$ which is the optimal linear reconstruction filter. Now this optimal filter minimises the equation :

\[J_t = \left| G_t X_t - X_0 \right|^2\] \[J_t = \left| G_t(\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}} \mathbf{X}_0 + \sqrt{1 - \bar{\alpha}} \epsilon )- X_0 \right|^2\]The equation is approximately equal to

\[J_t \approx \left| X_0 \right|^2 \left| 1 - \sqrt{\overline{\alpha}} \, G_t \right|^2 + ({1 - \overline{\alpha}}) \, \left| \epsilon \right|^2 \left| G_t \right|^2\]as $\epsilon$ and $X_0$ are uncorrelated. Here $\left| X_0 \right|^2$ is the power spectrum of $X_0$ and $\left| \epsilon \right|^2$ is the power spectrum of white noise which is equal to 1. So to find this optimal reconstruction filter, we differentiate this equation wrt $G_t$ and equate it to 0. We get,

\[\frac{\partial J_t}{\partial G_t} = 0 \implies \left| X_0 \right|^2 \left[ \left( 1 - G_t^* \sqrt{\overline{\alpha}} \right) \left( -\sqrt{\overline{\alpha}} \right) \right] + G_t^* (1 - \sqrt{\overline{\alpha}}) = 0\]This gives us

\[G_t^* = \frac{\sqrt{\overline{\alpha}}}{\overline{\alpha} + \frac{1 - \overline{\alpha}}{|X_0|^2}}\]Here $ G_t^* $ is the conjugate reconstruction filter. As it is real, $G_t^* = G_t$ . Hence, \(G_t = \frac{\sqrt{\overline{\alpha}}}{\overline{\alpha} + \frac{1 - \overline{\alpha}}{|X_0|^2}}\)

is the optimal linear reconstruction filter. The predicted $\hat{X}_0$ = $G_t \times X_t$. So predicted power spectrum \(|\hat{X}_0|^2 = |G_t|^2 |X_t|^2\)

\[|X_t|^2 \approx \, \overline{\alpha} |X_0|^2 + (1 - \overline{\alpha}) |\epsilon|^2 = \overline{\alpha} |X_0|^2 + 1 - \overline{\alpha}\]We can approximate it like This as $X_0$ and $\epsilon$ are uncorrelated. Now, let’s analyse the expression

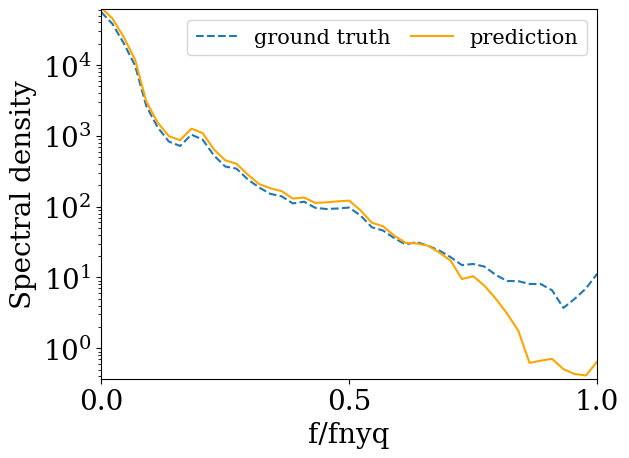

\[|\hat{X_0}|^2 = |G_t|^2 |X_t|^2 = \frac{\overline{\alpha} \, \left| X_0 \right|^4}{\left( \overline{\alpha} \, \left| X_0 \right|^2 + 1 - \overline{\alpha} \right)^2} \, \left( \overline{\alpha} \, \left| X_0 \right|^2 + 1 - \overline{\alpha} \right)\]Now, during the initial denoising stages, \(\bar{\alpha} \approx 0\). So in the low frequency region, $|X_0|^2$ is very high($|X_0|^2 \gg 1$). We make the assumption that \({\overline{\alpha}} \, |X_0| \approx 1\). So in the low frequency region, \(|\hat{X_0}|^2 \approx |X_0|^2\). In the high frequency region, $|X_0|^2$ is very low ($|X_0|^2 \to 0$). So, \(|\hat{X_0}|^2 \approx 0\). It can be clearly seen that in the inital denoising steps, the high magnitude signal is reconstructed while the low magnitude signal is approximated to zero.

In the later stages of the denoising process, \(\bar{\alpha} \approx 1\), so regardless of the magnitude of \(|X_0|^2\), the value of \(|\hat{X_0}|^2 \approx |{X_0}|^2\)

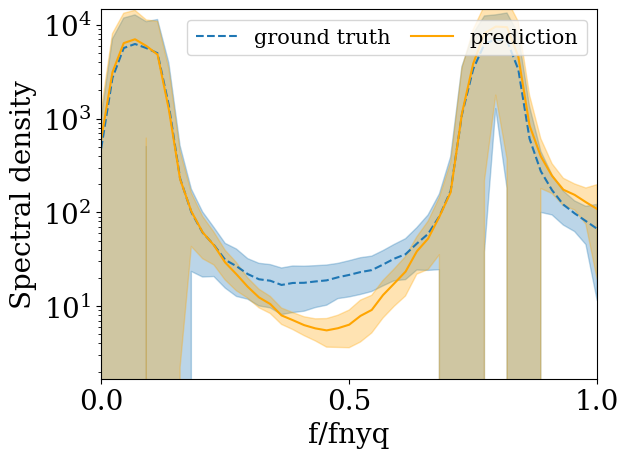

So we can clearly see that the model is succesfully able to learn the low frequency content in its initial denoising steps and eventually, given enough time steps, it learns the entire spectrum. But small models lack enough time steps and parameters, so only the low frequency spectrum is learnt well by the model and the predicted high frequency content is less than the ground truth. Note that the proof is based on the fact that the model has a hard time learning low magnitude regions in the power spectrum, which correspond to high frequency in natural images. But if we take a synthetic image which has low magnitude in the middle frequency region and high magnitude in the low and high frequency region, then as expected, the model fails to fit the middle region of the reduced spectrum properly. This can be seen below when we try to fit a synthetic image with two gaussian peaks by a small diffusion model

The model first fits the high magnitude regions and then tries to fit the low magnitude regions , which it fails to do as the number of timesteps are small.

There is another reason which might contribute to this bias. It is because the loss of a DDPM takes an expectation over the dataset.

\[\mathcal{L}_{\text{DDPM}} = \int p(\mathbf{x}_0) \, \mathbb{E}_{t, \epsilon} \left[ \left\| \epsilon - s(\mathbf{x}_t, t; \theta) \right\|_2^2 \right] d\mathbf{x}_0\]Most images have smooth features and there is a small perecntage of samples have high frequency components, hence p($\mathbf{x}_0$) for such samples is low and they are down weighted in the loss function

Mitigation of Frequency Bias Using Spectral Diffusion Model

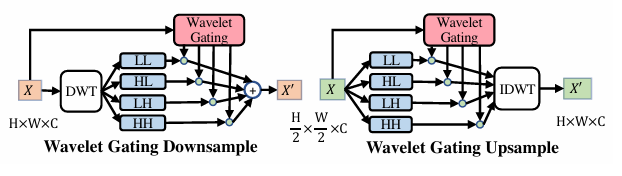

The main problem with diffusion models

The input image $X$ of size $H \times W \times C$ is divided into its corresponding 4 sub-bands (each of size $H/2 \times W/2 \times C$). Next, a soft-gating operation is used to weight these 4 sub-bands and the output feature $X’$ is produced as follows:

\[X' = \sum_{i \in \{LL, LH, HL, HH\}} g_i \odot X_i\]Here, $\odot$ represents element-wise multiplication. The gating mask is learnt using a feed-forward network.

\[g_{\{LL, LH, HL, HH\}} = \text{Sigmoid}(\text{FFN}(\text{Avgpool}(\mathbf{X})))\]In the WG-Up, the input feature is splitted into 4 chunks as the wavelet coefficients. Then, WG is carried out to re-weight each sub-band as before:

\[X' = \text{IDWT}(g_{LL} \odot X_{LL}, g_{LH} \odot X_{LH}, g_{HL} \odot X_{HL}, g_{HH} \odot X_{HH})\]Here IDWT is the inverse Discrete wavelet transform. Hence, they provide the model information of the frequency dynamics as well during training as the network decides which components to pay more attention to while learning the gating mask.

Another method that the authors apply is spectrum-aware distillation. They distill knowledge from a large pre-trained model into the WG-Unet. They distill both spatial and frequency knowledge into the WG-Unet using a spatial loss and a frequency loss. Let a noised image $X_t$ be passed into the network. The spatial loss is calculated as:

\[\mathcal{L}_{\text{spatial}} = \sum_{i} \| \mathbf{X}^{(i)}_T - \mathbf{X}^{(i)}_S \|^2_2\]where $\mathbf{X}^{(i)}_T$ and $\mathbf{X}^{(i)}_S$ stand for the pair of teacher/student’s output features or outputs of the same scale. A single $1 \times 1$ Conv layer is used to align the dimensions between a prediction pair.

The frequency loss is then calculated as :

\[\mathcal{L}_{\text{freq}} = \sum_i \omega_i \left\| \mathcal{X}_T^{(i)} - \mathcal{X}_S^{(i)} \right\|_2^2, \quad \text{where } \omega = \left| \mathcal{X}^{(i)} \right|^{\alpha}\]Here, $\mathcal{X}_T^{(i)}$, $\mathcal{X}_S^{(i)}$ and $\mathcal{X}_0^{(i)}$ represent the 2D DFT of $\mathbf{X}^{(i)}_T$, $\mathbf{X}^{(i)}_S$ and the resized clean image $X_0$ respectively. The scaling factor $\alpha$ is $-1$. We multiply the loss with $\omega_i$ as it gives more weight to high frequency content ($\mathcal{X}_0^{(i)}$ is low, hence $\omega_i$ is high) and less weight to low-frequency content.

So the final loss is:

\[\mathcal{L} = \mathcal{L}_{\text{DDPM}} + \lambda_s \mathcal{L}_{\text{spatial}} + \lambda_f \mathcal{L}_{\text{freq}}\]Here $\lambda_s$ = 0.1 and $\lambda_f$ = 0.1.

It was found that the frequency term in the loss function accounts for the largest change in FID, showing its importance in high-quality image generation. Thus using spectral knowledge during training helps a small network to produce high-quality realistic images and eliminate the ‘bias’ problem in diffusion models

Conclusion

In this article, we looked at another domain of viewing images and processing them i.e. the frequency domain. We then shed light into how the generative models posses certain biases in the frequency domain, particularly bias against high frequency content generation. We try to explain the reason behind this by breaking down the architecure of GANs