In Search of the Engram in LLMs: A Neuroscience Perspective on the Memory Functions in AI Models

Large Language Models (LLMs) are enhancing our daily lives but also pose risks like spreading misinformation and violating privacy, highlighting the importance of understanding how they process and store information. This blogpost offers a fresh look into a neuroscience-inspired perspective of LLM's memory functions, based on the concept of engrams-the physical substrate of memory in living organism. We discuss a synergy between AI research and neuroscience, as both fields cover complexities of intelligent systems.

Introduction

Large Language Models (LLMs) are increasingly prevalent, assisting with information retrieval, answering questions, and generating content. However, they’re a “double-edged sword”: while capable of remarkable feats, they also risk spreading misinformation, revealing sensitive data, or generating harmful content. Unlike traditional computer systems, where data storage is transparent and traceable, LLMs function more like “black boxes,” making it nearly impossible to pinpoint where specific information is stored and therefore challenging to edit. To effectively and efficiently edit models in this context, we need a clearer understanding of how memory is stored within these models and develop methodologies that allow for targeted editing.

In neuroscience, a field that studies highly complex systems like the biological brain, researchers have made significant progress in understanding memory formation and storage. Memory storage in neuroscience involves physical traces in the brain known as engrams, networks of neurons and synapses that “record” information after learning or an event. This process strengthens the connections between neurons that fire together based on synaptic plasticity, creating a lasting representation of that memory or skill

In this blog post, we will explore three key points to bridge the gap between neuroscience’s experimental findings and established theories about memory and the field of AI. In particular we will look into:

- How engrams are formulated in neuroscience,

- Two interesting works that seemingly track the engrams(memory locations) in LLMs

- The potential for LLM research and neuroscience to inspire one another

What is “Engram”?

Over a century ago, Richard Semon introduced the concept of the engram

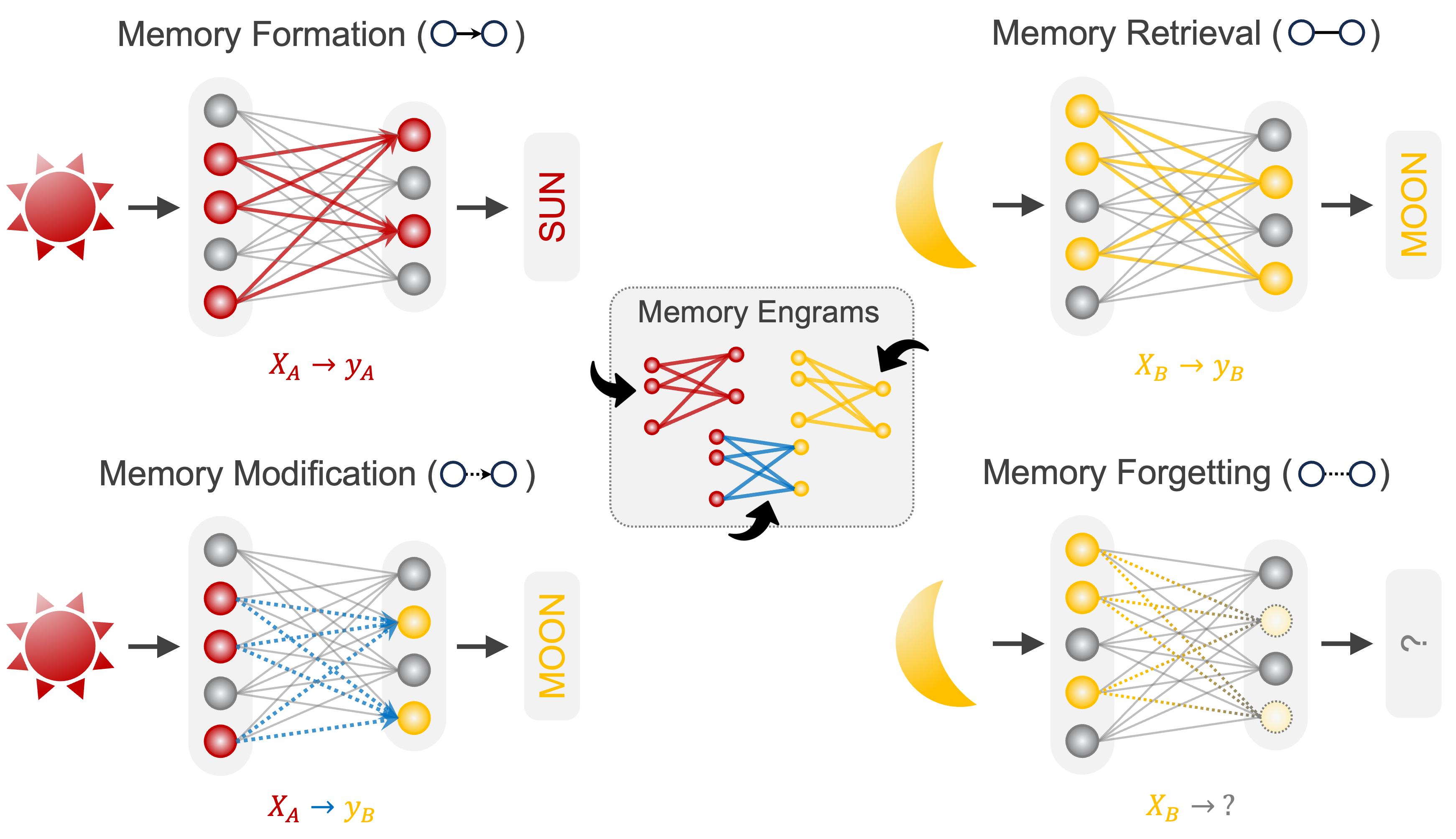

To understand engram, we must first define memory. Memories follow a dynamic life cycle with four key stages: formation, retrieval, modification, and forgetting (Fig. 1)

The search for engrams has long captivated neuroscience, dating back to Karl Lashley’s groundbreaking work. Lashley’s 1950 lecture, In Search of the Engram

Recent advances in neuroscience have made it possible to identify and manipulate engrams. Using optogenetics and advanced imaging techniques, researchers have successfully mapped the neural circuits associated with specific memories in animal models

The concept of engrams has shed light on how memories are formed, retrieved, modified, and forgotten (Fig. 1) and emphasizes the physical reality of memory as a process deeply embedded in the brain’s structure

This engram-based understanding could also serve as a model for artificial intelligence systems. If we could identify specific “engrams” within a neural network or large language model (LLM), we might be able to selectively edit or delete certain memories in AI models, similar to how neuroscientists can activate or deactivate specific memories in the brain experimentally. This cross-disciplinary exploration could open up new possibilities for making AI models more transparent, safe, and adaptable.

Explaining AI Research Through the Concept of Engrams

Having introduced the concept of engrams, we now examine LLM research through this lens. We have identified two research efforts that explore engram-like concepts in LLMs. The first is Grafting, a method that identifies and integrates specific parameter regions crucial for newly learned tasks. The second study is ROME (Rank-One Model Editing), which introduces targeted updates in LLMs without retraining the entire model. Although the original studies do not explicitly reference engrams, we are the first to bridge this concept to reinterpret and analyze their findings.

1. Grafting: Task-specific skill localization in LLMs

Panigrahi et al.(2023)

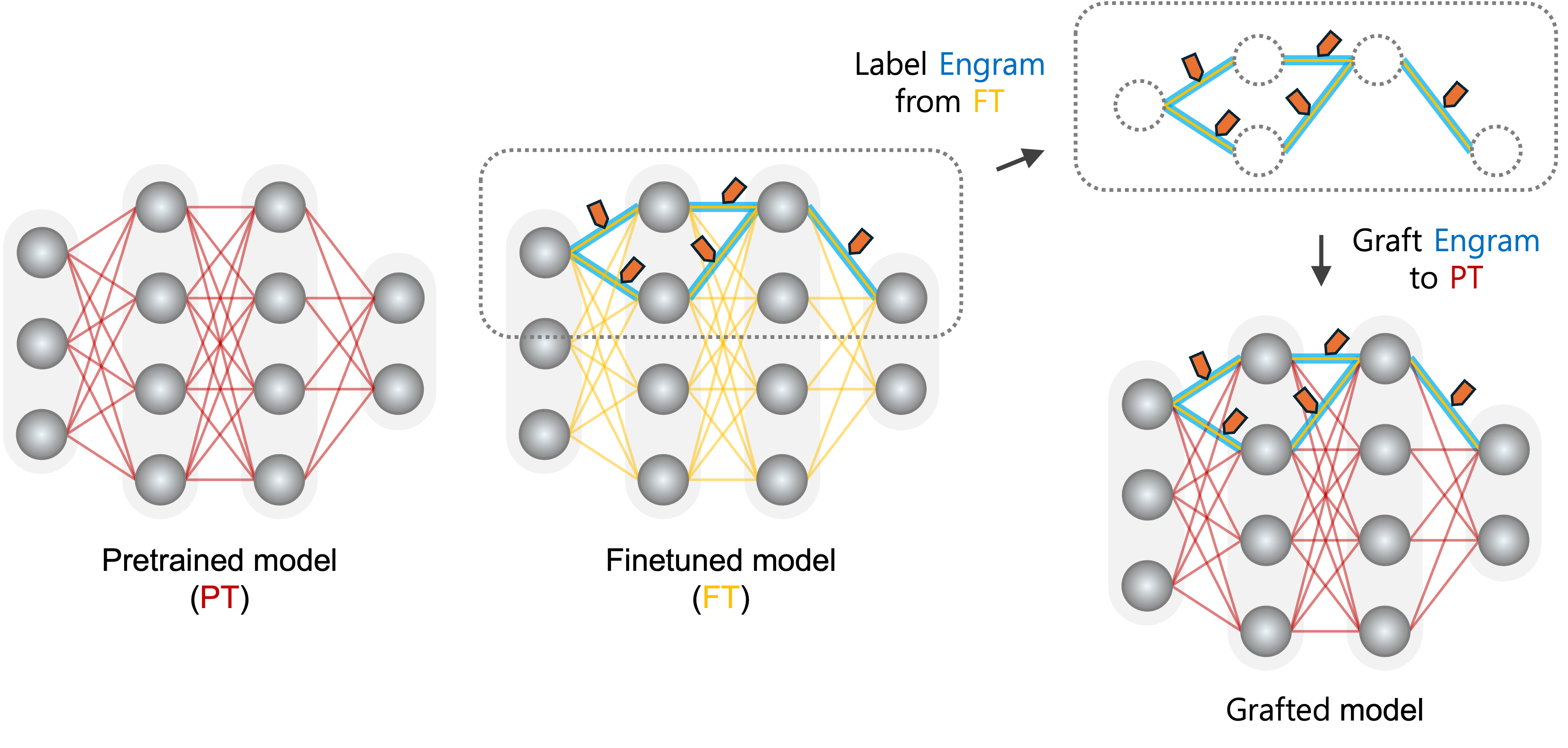

Connecting this work to neuroscience, we can consider this subset of weight parameters to be a synaptic engram for finetuning skills.(Fig. 2), An intriguing parallel can be drawn to the work of Hayashi-Takagi et al. (2015)

However, we also recognize differences in these two domains in terms of the methods used to identify and label the “synaptic engram.” In the model grafting process within the AI domain, the researchers directly computed the engram through optimization.

Finding synaptic engrams in LLMs

To localize the weight parameters or ‘engram’ that have an important contribution to the performance of the fine-tuned task (e.g., sentiment analysis), Panigrahi et al.(2023)

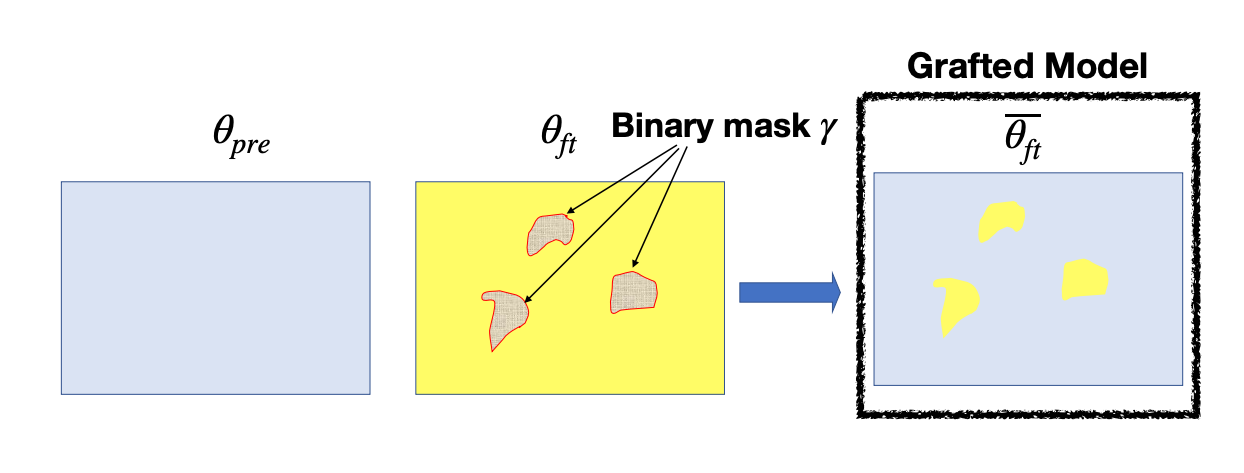

The grafted model is defined as:

\[\overline{\theta_{\textrm{ft}}}(\gamma) = \gamma \odot \theta_{\textrm{ft}} + (1-\gamma) \odot \theta_{\textrm{pre}}\]where \(\odot\) denotes element-wise multiplication. Figure 3 illustrates this equation.

So if the grafted model \(\overline{\theta_{\textrm{ft}}}(\gamma)\) has a similar performance to the fine-tuned model \(\theta_{\textrm{ft}}\), we can infer that the region in \(\theta_{\textrm{ft}}\), corresponding to \(\gamma\) is the engram responsible for the skill for the fine-tuned task.

To find this engram, they directly optimized the mask \(\gamma\) to minimize the task loss for the grafted model. Formally, this can be expressed as:

\[\underset{\gamma \in \{0, 1\}^{|\theta_{\textrm{ft}}|} : \|\gamma\|_{0} \le s}{\operatorname{argmax}} \mathcal{L}_{\mathcal{T}}(\gamma \odot \theta_{\textrm{ft}} + (1 - \gamma) \odot \theta_{\textrm{pre}})\]where \(\mathcal{L}_{\mathcal{T}}\) is a metric for performance on the Task \(\mathcal{T}\) (e.g., classification error), and \(s\) is a sparsity constraint on the mask \(\gamma\).

To enable optimization through gradient descent, they reparameterized the mask \(\gamma\) as a differentiable variable using a sigmoid function applied to a real-valued vector \(S\), i.e., \(\gamma = \sigma(S)\).

Using this optimization objective directly, they successfully identified task-specific skill engrams. By grafting just 0.01% of \(\theta_{\textrm{ft}}\) (the identified engram) onto \(\theta_{\textrm{pre}}\), \(\overline{\theta_{\textrm{ft}}}(\gamma)\) achieved over 95% of the original fine-tuned model’s performance. This confirms that the identified engram is indeed responsible for the task-specific skill.

Leveraging Engrams in LLMs

In the AI domain, researchers have demonstrated how memory locations (i.e., engrams) can be identified through direct optimization techniques. Once these task-specific engrams are identified, they can be applied to practical scenarios like continuous learning. Panigrahi et al.(2023)

Identifying engrams in LLMs opens up a wide range of possibilities, including targeted memory editing. In the following section, we will delve into research that has explored memory editing techniques in LLMs.

2. ROME: Targeted Memory Editing in LLMs

Meng et al. (2022)

Finding engram cells

To edit a specific fact in the model, the authors first identified where that fact, or “engram,” is stored. Much like neuroscientists reactivating tagged engram cells to probe stored memories

Injecting a False Memory

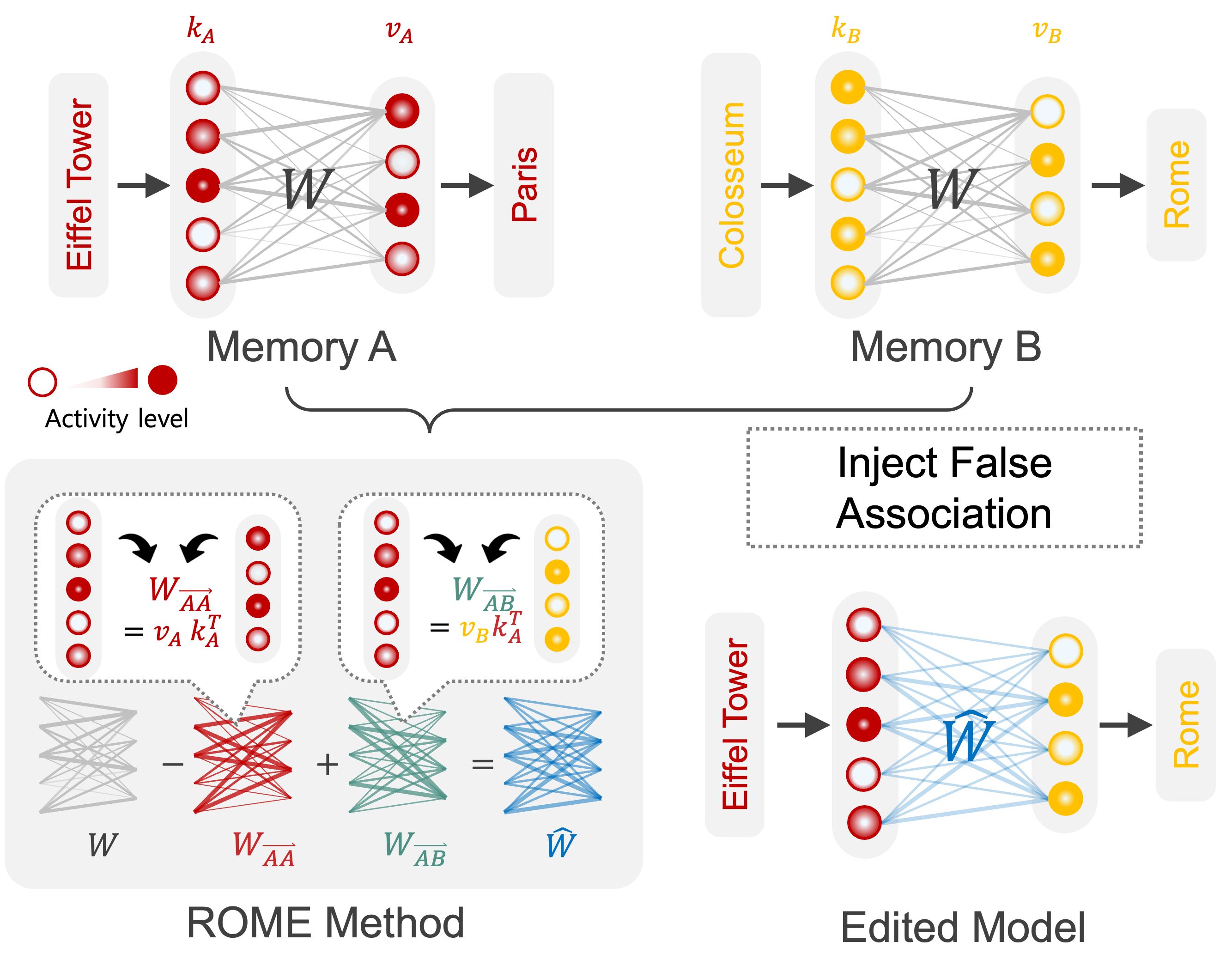

Suppose memory A encodes the factual association “The Eiffel Tower is located in Paris,” and memory B encodes the factual association “The Colosseum is located in Rome.” (See Fig. 4 Top) Now, we want to inject a false memory into the model, such as “The Eiffel Tower is located in Rome.” To do this, we need to identify the specific engram and its corresponding firing pattern. The authors hypothesize that the MLP module can be modeled as linear associative memories. In the output linear layer of an MLP, a vector \(k\) serves as the input, and the value vector \(v = Wk\), where \(W\) represents the linear associative memory.

To determine the firing pattern \(k_A\) for engram A, researchers use the prompt “The Eiffel Tower is located in” combined with various prefixed contexts. They calculate the \(k_A\) vector at the middle MLP layer where the factual association engram is located by averaging activity patterns generated from inputs with different prefixes, such as “The first thing. {prompt}” and “A few days ago. {prompt}.” By averaging the responses to these prefixed inputs, they obtain a reliable estimate of the \(k_A\) vector that represents the engram’s pattern in that layer. The corresponding value vector for this pattern is \(v_A = Wk_A\), which leads the model to output “Paris.”

Next, to implant the false memory, the model modifies the output neurons \(v\) using optimization techniques to create a new vector \(v_B\) that leads the model to a false output “Rome.” By using gradient descent, \(v\) is iteratively adjusted until \(v_B\) reliably corresponds to “Rome.”

After finding the firing patterns \(k_A\) and \(v_B\), the authors proposed a rank-one model editing (ROME) method (See Fig. 4 bottom). This method produces a weight change matrix, \(\Delta W\), which is then added to the original weight matrix, resulting in an updated matrix: \(\hat{W} = W + \Delta W\), where

\[\Delta W = \eta (v_B k_A^{T} - W k_A k_A^{T})C^{-1}\]Here, \(C\) approximates the covariance of existing key vectors and \(C^{-1}\) is the inverse of the covariance matrix, directing the weight update in a way that minimizes changes to unrelated facts, and \(\eta\) is a constant.

In neuroscience, Hebbian learning is summarized by “neurons that fire together, wire together.” Mathematically, this is often modeled as:

\[\Delta w_{ij} = \eta x_i y_j\]where \(w_{ij}\) is the weight of the connection between neuron \(i\) and neuron \(j\), \(x_i\) and \(y_j\) are the activations of neurons \(i\) and \(j\), and \(\eta\) is a learning rate.

This rule is similar to the update rule in ROME.

\[\Delta w_{ij} \propto [v_B k^{T}_A - W k_A k^{T}_A]_{ij} = (v_B)_i (k_A)_j - (v_A)_i (k_A)_j\]In addition to injecting a new association (\(v_B k_A^{T}\)), ROME also effectively “removes” the old association by subtracting \(v_A k_A^{T}\). This process resembles anti-Hebbian unlearning, as it eliminates the previous association to ensure it is fully replaced by the new one. This update rule aligns ROME with the principle of “engram cells that fire together, wire together”

The theoretical foundations of the ROME method align with biological mechanisms demonstrated in neuroscience experiments. For instance, Ohkawa et al. (2015)

This mechanism resembles the ROME method’s approach of pairing a specific \(k_A\) (representing the “neutral context” of the Eiffel Tower in Paris) with a new \(v_B\) (representing the fear-associated memory, or in this case, Rome). Both rely on synchronizing distinct ensembles—whether neurons in the brain or patterns in an artificial model—to generate a qualitatively new association.

The findings from Ohkawa et al.

This exploration of the underlying mathematical framework reveals that ROME is not merely an engineering technique; it represents a sophisticated application of associative memory principles in AI.

Concluding Remarks: Let’s connect AI research with neuroscience!

This blog gave a new interpretation of two LLM studies through the lens of neuroscience. Interestingly, although neuroscience and AI are conducted independently, LLM research can be viewed through the framework of neuroscience.

LLMs are highly complex systems, and it is challenging to understand their processes and handling of information. Similarly, the brain is an equally complex system. Researchers in both domains may share a common goal: to understand these intricate “black box” systems. Achieving this understanding could enable us to edit or control LLMs to prevent harmful behaviors. In neuroscience, such insights could contribute to treatments for Alzheimer’s disease and other brain-related conditions.

We are fascinated to find connection of the two introduced AI research with engrams. Moving forward, by integrating neuroscience insights with cutting-edge AI research, we may be able to uncover new ways to make LLMs more transparent, adaptable, and safe for everyday use. This effort might bring us closer to a future where AI models are as understandable and trustworthy as we hope our own minds can be.