Positional Embeddings in Transformer Models: Evolution from Text to Vision Domains

Positional encoding has become an essential element in transformer models, addressing their fundamental property of permutation invariance and allowing them to understand sequential relationships within data. This blog post examines positional encoding techniques, emphasizing their vital importance in traditional transformers and their use with 2D data in Vision Transformers (ViT). We explore two contemporary methods—ALiBi (Attention with Linear Biases) and RoPE (Rotary Position Embedding)—analyzing their unique approaches to tackling the challenge of sequence length extrapolation during inference, a significant issue for transformers. Additionally, we compare these methods' fundamental similarities and differences, assessing their impact on transformer performance across various fields. We also look into how interpolation strategies have been utilized to enhance the extrapolation capabilities of these methods; we conclude this blog with an empirical comparison of ALiBi and RoPE in Vision Transformers. To the best of our knowledge, this represents the first direct comparison of these positional encoding methods with those used in standard Vision Transformers.

Background

“Attention Is All You Need,” introduced by (Vaswani et al. [2017]

Later, (Dosovitskiy et al. [2021]

(Vaswani et al. [2017]

Preliminaries

Self-Attention Mechanism:

The self-attention mechanism processes sequences by representing each element as a vector of embedding dimension \(d\). For a sequence of length \(L\) and embedding dimension \(d\), the input is represented as a matrix \(X \in \mathbb{R}^{L \times d}\).

The mechanism employs three learnable weight matrices: \(W_Q,W_K,\) and \(W_V\) \(\in \mathbb{R}^{d \times d_{model}}\), where \(d_{model}\) represents the dimensionality of the projected subspaces. These matrices transform the input into queries, keys, and values respectively:

\[Q = X\,W_Q \;\;\;\;\;\;\;\; K = X \, W_K \;\;\;\;\;\;\;\; V = X \, W_V\]The attention matrix is computed using the following formula:

\[\text{Attention}(Q, K) = \text{softmax}(QK^T/√d_{model})\] \[\mathbf{Z} = \text{Attention}(Q, K) \cdot V\]With respect to each token, let \(x_i\) be the context vector for \(i^{\text{th}}\) token, the corresponding query, key and value vectors, \(\mathbf{q_i}, \mathbf{k_i}\) and \(\mathbf{v_i}\) are defined as follows:

\[\mathbf{q_i} = x_i \: W_Q \; \; \; \; \; \; \mathbf{k_i} = x_i \: W_K \; \; \; \; \; \; \mathbf{v_i} = x_i\:W_V\]and \(N\) being total number of tokens , the attention score between the \(m_{th}\) token (query) and the \(n_{th}\) token (key) is formulated as

\[a_{m,n} = \frac{\exp\left( \frac{\mathbf{q}_m \mathbf{k}_n^\top}{\sqrt{d}} \right)}{\sum_{j=1}^{N} \exp\left( \frac{\mathbf{q}_m \mathbf{k}_j^\top}{\sqrt{d}} \right)}\]and \(\mathbf{z}_m\) (output vector) for the \(m_{th}\) token is calculated as

\[\mathbf{z}_m = \sum_{n=1}^{N} a_{m,n} \mathbf{v}_n\]Multi-Head Attention

In multi-head attention, the computation is extended across h parallel attention heads. Each \(head_i\) operates as:

\[\text{head}_i = \text{Attention}(Q\,W_Q^i, K\,W_K^i, V\,W_V^i)\]The outputs from all heads are concatenated and projected back to the original dimensionality:

\[\text{MultiHead}(Q, K, V) = \text{Concat}(\text{head}_1,\ldots,\text{head}_h)\:W_O\]where \(W_O \in \mathbb{R}^{hd_k \times d_{model}} , W_i^Q \in \mathbb{R}^{d_{\text{model}} \times d_k} , W_i^K \in \mathbb{R}^{d_{\text{model}} \times d_k}, \ W_i^V \in \mathbb{R}^{d_{\text{model}} \times d_k}, \ \text{and } W^O \in \mathbb{R}^{h d_k \times d_{\text{model}}}\) are learned matrices. Note \(d_{model} = h \times d_{k}\) and \(Q,K,V \in \mathbb{R}^{ L\times d_{\text{model}}}\)

Absolute Positional Embeddings

Absolute Positional embedding was introduced by (Vaswani et al. [2017]

Where \(p_i\) is the positional embedding vector and \(x_i\) is the context vector corresponding to the \(i_{th}\) token. Note that \(x '_i,x_i ,p_i \in \mathbb{R}^d\). (Vaswani et al. [2017]

where \(p_{i,t}\) is the \(t^{th}\) element in the \(p_i\) vector.

One might question why a function of sines and cosines was chosen to represent positional encodings in a sequence—why not any other arbitrary function? The choice of sinusoidal functions was actually a strategic one, offering several advantages that benefit transformer models:

- Firstly the values are normalized between \([-1,1]\) allowing the model to learn parameters easily.

- The distance between neighboring positions is symmetrical and decays naturally with position.

- The formulation shows that every two consecutive elements in the embedding \(p_i\) share the same frequency denominator. For a pair with frequency \(w_k\), we can demonstrate that

Hence the dot product \(p_i \cdot p_{i+\phi}\) is independent of position \(i\), and relative position \(\phi\) is retained. This consistency allows the model to capture regular intervals and patterns, making it especially effective for tasks requiring sequential dependencies.

The authors hypothesized that sinusoidal positional encoding would enable the model to learn relative positions naturally, thanks to the properties outlined above, and might also allow it to extrapolate to sequence lengths longer than those seen during training. This rationale led to sinusoidal positional embeddings being one of the first methods adopted in transformer architectures.

However, subsequent research challenged these assumptions. Studies found that absolute sinusoidal positional encoding was not well-suited for capturing relative positional information effectively (Shaw et al. [2018]

Learned Positional Embeddings

In addition to sinusoidal positional embedding, (Vaswani et al. [2017]

Relative Positional Embeddings

Unlike absolute positional encodings, which create embeddings for each position independently, relative positional embeddings focus on capturing the pairwise relationships between tokens in a sequence. Also rather than directly adding the embeddings to the context vectors, the relative positional information is added to keys and values during the attention calculation. Hence

\[\mathbf{q_m} = x_m \:W_Q \; \; \; \; \; \; \mathbf{k_n'} = (x_n+ \tilde{p}_r^k)\:W_K\; \; \; \; \; \; \mathbf{v_n'} = (x_n+ \tilde{p}_r^v)\:W_V\]where \(\tilde{\mathbf{p}}_r^k, \tilde{\mathbf{p}}_r^v \in \mathbb{R}^d\) are trainable relative positional embeddings and \(r = clip(m-n, Rmin, Rmax)\) represents the relative distance between the two tokens at positions $m$ and $n$. The maximum relative position is clipped, assuming a precise relative position is not useful beyond a certain distance. Further, clipping the maximum distance enables the model to extrapolate at inference time. However, this approach may not encode useful information about the absolute position of the token, which is useful in 2D tasks like Image Classification (Islam et al. [2019]

Positional encoding in Vision Transformers

Motivated by the success of transformers in processing one-dimensional textual data, (Dosovitskiy et al. [2021]

Rotary Positional Embeddings

Traditional positional encoding methods have primarily involved adding positional information directly to context embeddings. While this approach introduces a positional bias, it can limit the depth of interaction with attention weights, potentially underutilizing valuable relative position information. Additionally, since this information is added after the query-key multiplication, it does not contribute to the critical query-key similarity calculations that influence attention mechanisms.

Then came RoFormer (Su et al. [2021]

The mechanism of RoPE

Given the limitations of directly adding positional information, we need a formulation that encodes relative position information within the attention mechanism by applying a transformation solely to the query and key vectors.

Let token at position \(m\) has the context embeddings \(x_m\) , we define function \(f(x_m,m)\) which takes the context vector \(x_m\) and its position in the sequence \(m\) and returns a transformed embedding having the positional information. We want the function \(f\) to be such that the dot product of two embeddings depends on their relative position to each other i.e.

\[f(x_m,m)\cdot f(x_n,n) = g(x_m,x_n,m-n)\]The two-dimensional case

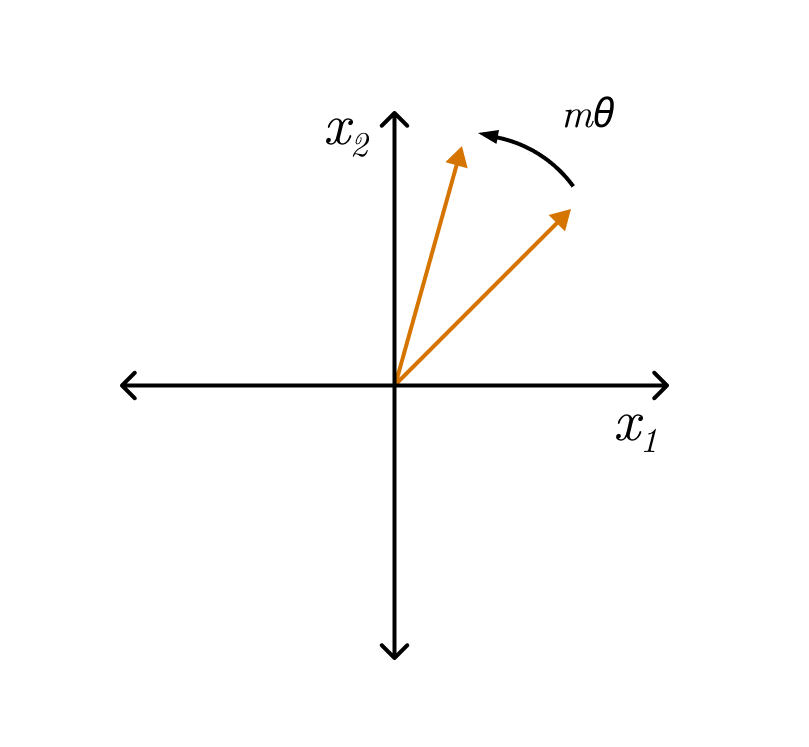

Consider the basic case where context vector \(x_m = \begin{pmatrix} x_m^{(1)} &x_m^{(2)}\end{pmatrix}^T\) is 2 dimensional and in complex space it can be represented as \(x_m^{(1)} + ix_m^{(2)}\) . For the exponential function, we know that \(e^m \cdot e^n = e^{m+n}\) which is very similar to the properties we want from the function \(f\). Thus for defining \(f\), we can multiply \(f\) \(x_m\) with \(e^m\) , but there is one problem that is explosion of magnitude as the sequence grows. Hence \(e^{im\theta}\) is an ideal choice for multiplication, as it doesn’t cause any magnitude changes and rotates the vector \(x_m\) by an angle of \(m\theta\).

\[f(x_m,m) = x_m e^{im \theta}\]Formally, in order to encode the positional information, the key \(k_m\) at position \(m\) and query \(q_n\) at position \(n\) are multiplied with \(e^{im\theta}\) and \(e^{in\theta}\) respectively as a transformation. Consequently, the \((m,n)^{th}\) element of the attention matrix becomes -

\[q_n' = q_ne^{in \theta} \; \; k_m' = k_me^{in\theta}\] \[A'_{(n,m)} = \text{Re}[q^{'}_nk^{'*}_m] = \text{Re}[q_nk^*_me^{i(n−m)θ}] \;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\; \scriptstyle \text{where Re[z] is the real part of z}\]Hence the \(e^{i(n−m)θ}\) in this formulation of attention is responsible injecting relative position of the tokens which are \((n-m)\) distance apart from each other. The formal derivation that it is a solution to equation formulated is detailed in RoFormer (Su et al. [2021]

- Stability of Vectors: Adding tokens at the end of a sentence doesn’t affect the vectors for words at the beginning, facilitating efficient caching.

- Preservation of Relative Positions: If two words, say “pig” and “dog,” maintain the same relative distance in different contexts, their vectors are rotated by the same amount. This ensures that the angle, and consequently the dot product between these vectors, remains constant.

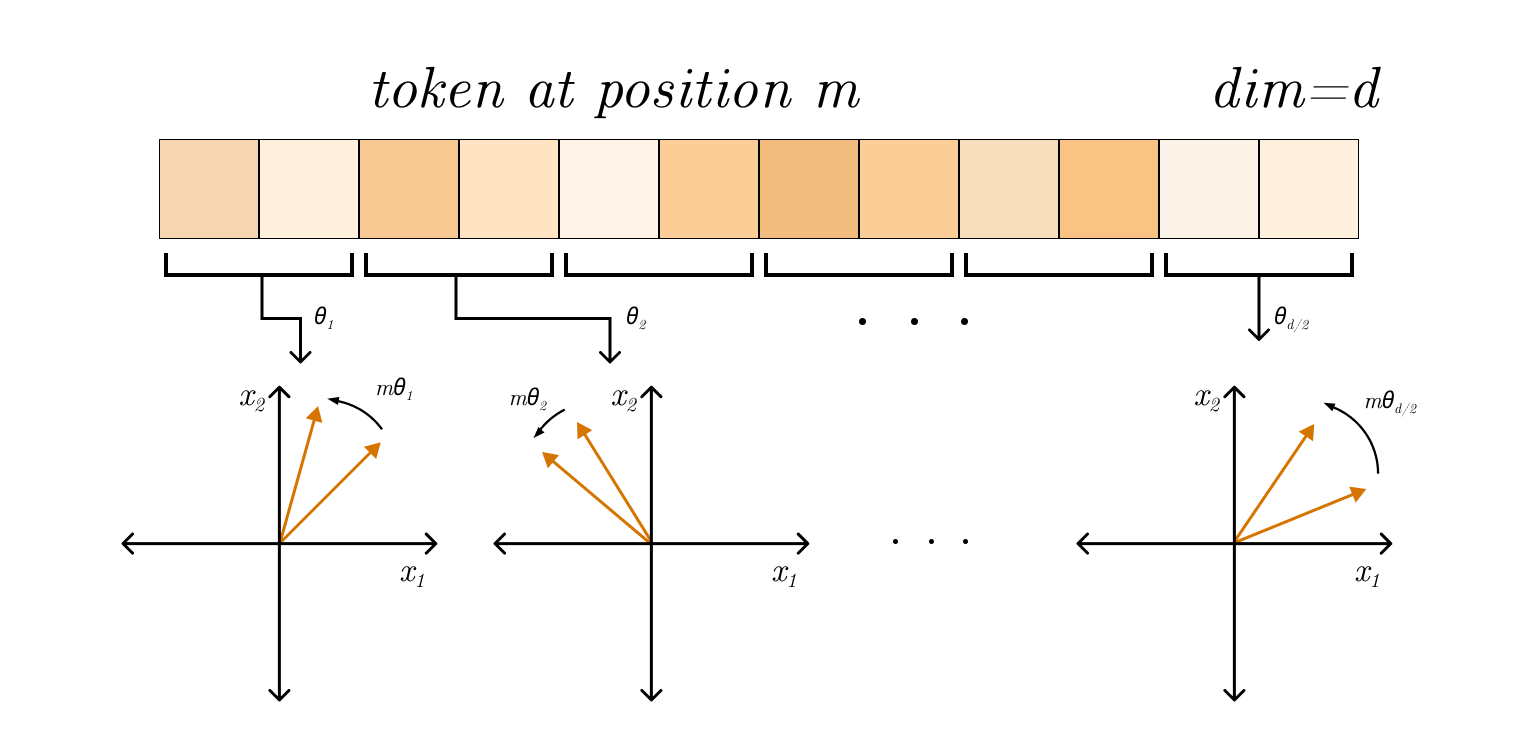

The general D-dimensional case

The idea of extending the 2D result to the d dimensional case is to break the embedding vector in various 2 dimensional chunks and rotate each one of them by a specific angle \(m\theta_i\) where m depends on the position of token in the sequence and \(\theta_i\) varies according to the chunk. This can be intuitively thought of as a corkscrew rotation in higher dimensions.

More formally, we divide the d dimensional space into smaller 2 dimensional subspaces, apply the rotation in those smaller subspaces and combine them again, this can be achieved through

\[q_n = R^{d}_{\Theta,n}\:W_q\:x_n, \; \; \; \;k_m = R^{d}_{\Theta,m}\:W_k\:x_m\]where the transformation matrix \(R^{d}_{\Theta,m}\) is defined as follows -

\[R^{d}_{\Theta,m} = \begin{pmatrix} \cos m\theta_1 & -\sin m\theta_1 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & 0 & 0 \\ \sin m\theta_1 & \cos m\theta_1 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \cos m\theta_2 & -\sin m\theta_2 & \cdots & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \sin m\theta_2 & \cos m\theta_2 & \cdots & 0 & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & \cos m\theta_{d/2} & -\sin m\theta_{d/2} \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & \sin m\theta_{d/2} & \cos m\theta_{d/2} \end{pmatrix}\]where the frequencies \(\theta_t\) are defined as follows -

\[\theta_t = 10000^{-t/(d/2)} \; \; \; \; \; t \in \{0,1, \cdots,d/2\}\]This sums up the mathematical generalization for the d dimensional case of rotary positional embeddings. In order to make the notations simpler and easier to digest, we take an equivalent representation in complex space. Given the query and key vectors \(q_n, k_m \in \mathbb{R}^d\), we define complex vectors \(\bar{q_n}, \bar{k_m} \in \mathbb{C}^{d/2}\) by considering the \(2t^{th}\) dimension as real part and \(2t+1^{th}\) dimension as the complex part of the vector.

That is if \(q_n = (q^1_n,q^2_n,q^3_n,q^4_n, \cdots,q^{d-1}_n,q^d_n)\) then \(\bar{q_n} = (q^1_n+iq^2_n,q^3_n+iq^4_n, \cdots,q^{d-1}_n+iq^d_n) \in \mathbb{C}^{d/2}\) is its complex space counterpart, similar for key vectors. Now it can be proved that

\[q_nk_m^T = \operatorname{Re}[\bar{q_n} \bar{k_m}^T]\]Using this idea of complex vectors, we can define a new transformation matrix \(\textbf{R} \in \mathbb{C}^{N \times (d/2)}\) as

\[\textbf{R}(n,t) = e^{i\theta_tn} \;\;\;\;\;\;\;\; \text{or} \;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\textbf{R}(n) = \begin{pmatrix} e^{i\theta_1m} \\ e^{i\theta_2m} \\ \vdots \\ e^{i\theta_{d/2-1}m} \\ e^{i\theta_{d/2}m} \end{pmatrix}\]and the transformation of RoPE can be reformed with Hadamard Product \(\circ\) as

\[\bar{q}' = \bar{q} \circ \textbf{R}, \; \; \; \; \bar{k}' = \bar{q} \circ \textbf{R}, \; \; \; \; \textbf{A}' = \operatorname{Re}(\bar{q_n} \bar{k_m}^T)\]Where Hadamard product is the operation of taking element wise multiplication of corresponding matrices. We will be using this summarized notation to further define axial and mixed RoPE Positional Embeddings for ViT in later sections.

RoFormer (Su et al. [2021]

RoPE in Vision Trasformers

(Heo et al. [2024]

Axial 2D Rope

The core idea is to take and divide the embedding dimension into two and apply positional embedding for x-axis and y-axis separately, which is just repeating the 1d embedding twice. For indexing let patch positions in 2d image be \(\textbf{p}_n = (p_n^x, p_n^y)\) then the rotation matrix \(\textbf{R}\) from earlier section can be defined as

\[\textbf{R}(n,2t) = e^{i\theta_tp_n^x}, \; \; \; \; \textbf{R}(n,2t+1) = e^{i\theta_tp_n^y}\]Hence we are interwining the rope along the two axes \(x\) and \(y\). As the range of indexes \((p_n^x, p_n^y)\) are reduced by square root, the RoPE frequencies \(\theta_t\) are also reduced by square root, i.e.

\[\theta_t = 100^{-t/(d/4)}, \;\;\;\;\;\text{where} \; t \in \{0,1,\cdots, d/4\}\]Note that frequencies \(\theta_t\) for vision tasks are much larger than those used for language tasks. Also number of frequencies is halved so that \(d/2\) is covered by the contribution of both axes \(x,y\).

Mixed RoPE

The axial frequencies are unable to handle diagonal directions since frequencies only depend on either $x$ or $y$ axes. As the relative positions in RoPE are embedded in the form of \(e^{i\theta_t(n-m)}\) the relative positions are always interpreted as either \(e^{i\theta_t(p_n^x-p_m^x)}\) or \(e^{i\theta_t(p_n^x-p_m^x)}\), so the axial frequencies are not mixed in the axial direction.

In order to cater for mixed frequencies, the new rotation matrix \(\textbf{R}\) is proposed as

\[\textbf{R}(n,t) = e^{i(\theta_t^xp_n^x+\theta_t^yp_n^y)}\]Unlike 1D RoPE and axial frequency RoPE, Mixed RoPE doesn’t define frequencies explicitly. Instead, it allows the network to learn frequencies \((\theta_t^x,\theta_t^y)\) for \(t \in \{0, 1, \cdots, d/2\}\) , as these are treated as learnable parameters. Separate sets of frequencies are used per head per self attention layer.

While RoPE tries to tackle the problems of Absolute and Learned positional encoding, another method that addresses this fundamental question in the realm of transformer models, i.e., “how to achieve extrapolation at inference time for sequences that are longer than those encountered during training,” is Alibi(Attention with linear bias) introduced by (Press et al. [2021]

Attention with Linear Biases (Alibi)

Unlike RoPE’s rotary approach, ALiBi introduces a novel mechanism for incorporating positional information into transformer models. The key innovation lies in its integration of positional encoding directly within the attention computation rather than at the token embedding level. This approach significantly differs from the previous one, focusing on relative positional relationships through a bias-based attention mechanism. One of ALiBi’s standout features is its complete removal of traditional positional embeddings at the input layer. Instead of adding positional encodings at the bottom of the network, ALiBi integrates them as biases within the attention layers themselves.

Mechanism and Architecture

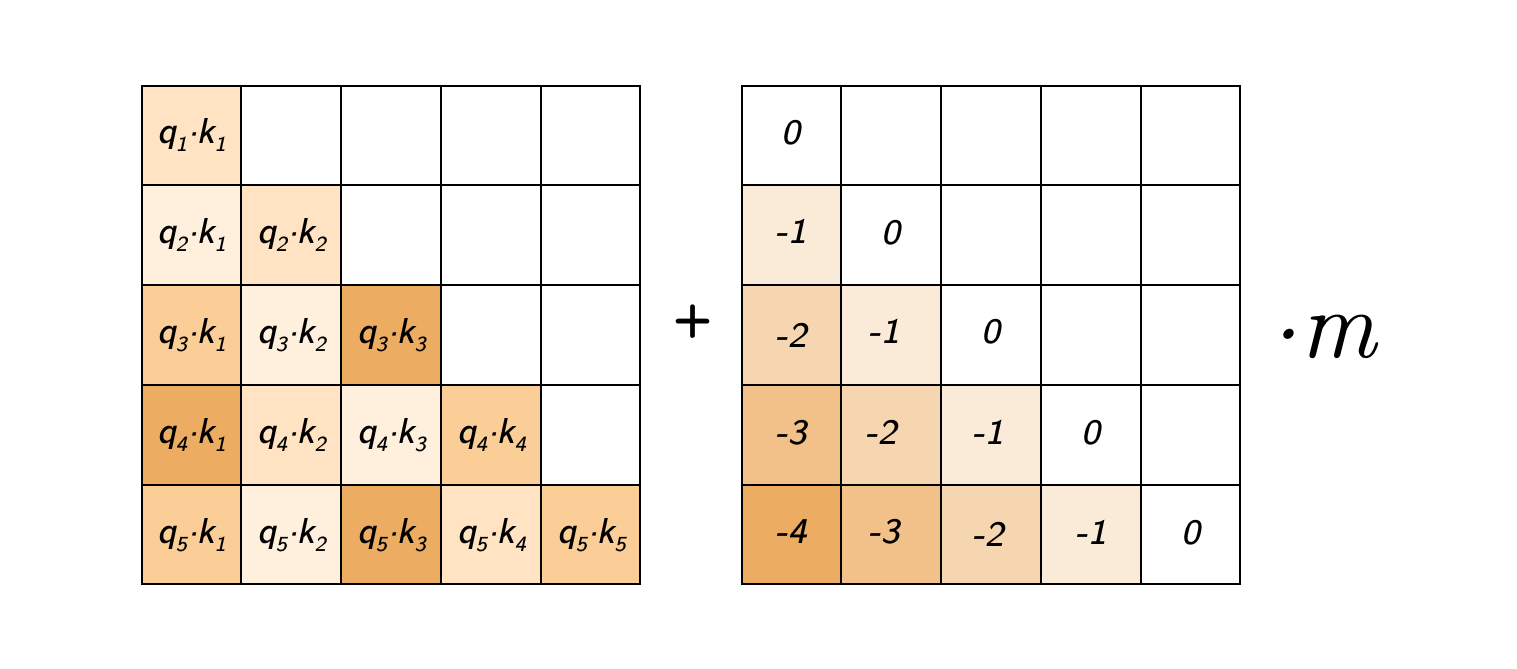

ALiBi operates by injecting positional information through a bias matrix added to the self-attention scores before the softmax operation. The magnitude of this bias is proportional to the distance between the query and key tokens, establishing an intrinsic relationship between position and attention strength. Mathematically, this transforms the standard attention computation by introducing a position-aware bias term.

The architecture proposed by (Press et al. [2021]

What is \(\textbf{m}\) ?

\(\textbf{m}\) is a non-learnable, head-specific slope parameter whose values follow a geometric sequence defined that starts at \(2^{-\frac{8}{n}}\) and uses that same value as its ratio, where \(n\) represents the number of attention heads.

This choice of slope values offers several benefits:

- Diverse Temporal Scales: Each attention head is able to focus on different temporal scales, allowing the model to capture a range of positional relationships.

- Ensemble Effect: The varied attention patterns create an ensemble-like effect, enriching the model’s representational power.

- Contextual Flexibility: With slopes customized for different scales, the model can apply the most effective attention mechanisms for different contexts, adapting to both short and long-range dependencies.

Theoretical Foundation and Advantages

The core principle behind ALiBi lies in temporal relevance—a systematic adjustment of attention values based on the positional distance between queries and keys. This mechanism introduces an inductive recency bias, which has several advantages:

- Proportional Penalties: ALiBi applies penalties to attention scores based on the distance between tokens, with closer tokens receiving lower penalties and more attention.

- Enhanced Focus on Proximity: The method imposes stronger penalization on distant token relationships, naturally biasing the model toward more relevant, nearby tokens.

- Adaptive Penalization Across Heads: ALiBi allows each attention head to apply different penalty rates, enabling the model to capture both short-range and longer-range dependencies effectively.

Performance and Extrapolation

A standout feature of ALiBi is its remarkable ability to extrapolate to sequence lengths far beyond those seen during training. Unlike traditional positional encoding methods, ALiBi sustains robust performance even as sequence lengths grow significantly. This capability overcomes a fundamental limitation in standard transformer architectures, representing a major advancement in the scalability and adaptability of attention-based models.

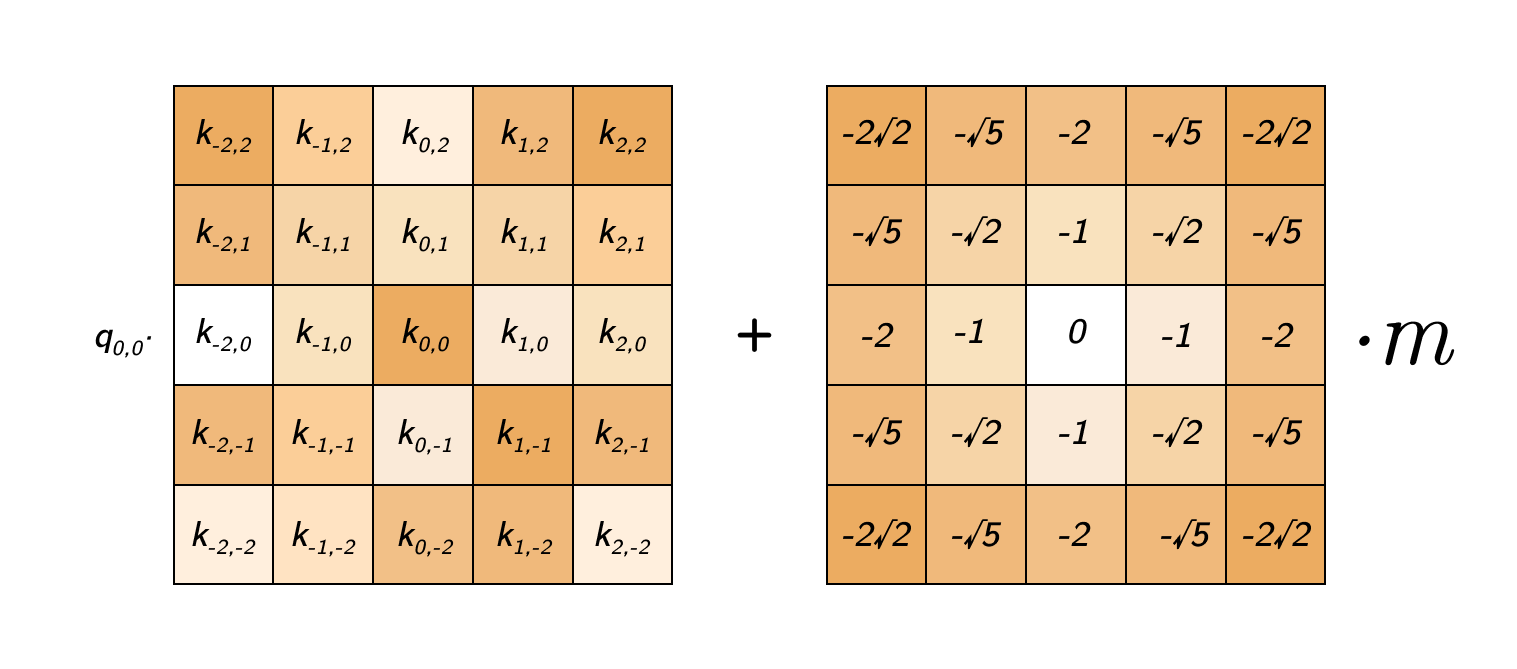

Alibi in Vision Transformers

Building on ALiBi’s success with sequential data, researchers extended its application to two-dimensional image data in Vision Transformers (ViT). Translating ALiBi from 1D to 2D domains posed some challenges like adapting its causal attention mechanism for general self-attention and designing spatially aware 2D penalty metrics. These adjustments enabled ALiBi to effectively capture spatial dependencies in images, expanding what positional encoding can do in vision models.

Two-Dimensional Adaptation

The adaptation to 2D data, proposed by (Fuller et al. [2023]

- Symmetric Attention Structure: Unlike the lower triangular matrix in sequential processing, the 2D implementation employs a symmetric attention matrix, reflecting the bidirectional nature of spatial relationships in images.

-

Spatial Distance Metrics: The linear distance penalty is replaced by a Euclidean metric that captures 2D spatial relationships between image patches: \(\text{distance_penalty} = \sqrt{(x_2 - x_1)^2 + (y_2 - y_1)^2} \cdot m\)

where \(m\) retains its role as a non-learnable head-specific parameter.

Comparative Analysis: RoPE and ALiBi

These two approaches, while sharing certain fundamental principles, represent distinct philosophical approaches to positional encoding:

Shared Characteristics

- Both RoPE and ALiBi on the principle of not adding positional encoding to word embedding, instead focusing on modifying the attention weights computed at every layer. This aligns with the thought that positional information and semantic information represent different things and that they should not be mixed.

- Both incorporate distance-dependent attention penalties. Both have an inductive recency bias and work on the philosophy that the farther a token is from a given token, the less relevant it is.

Key Distinctions

- Mathematical Foundation

- RoPE employs trigonometric transformations with theoretical guarantees. It uses the embedding vector’s rotation to capture positional information, while ALiBi utilizes straightforward linear distance penalties for encoding positional information.

- Extrapolation Strength

- Alibi demonstrates strong extrapolation capability, while RoPE struggles to extrapolate well enough above a number of tokens based on what it has been trained on.

Extrapolation via Interpolation

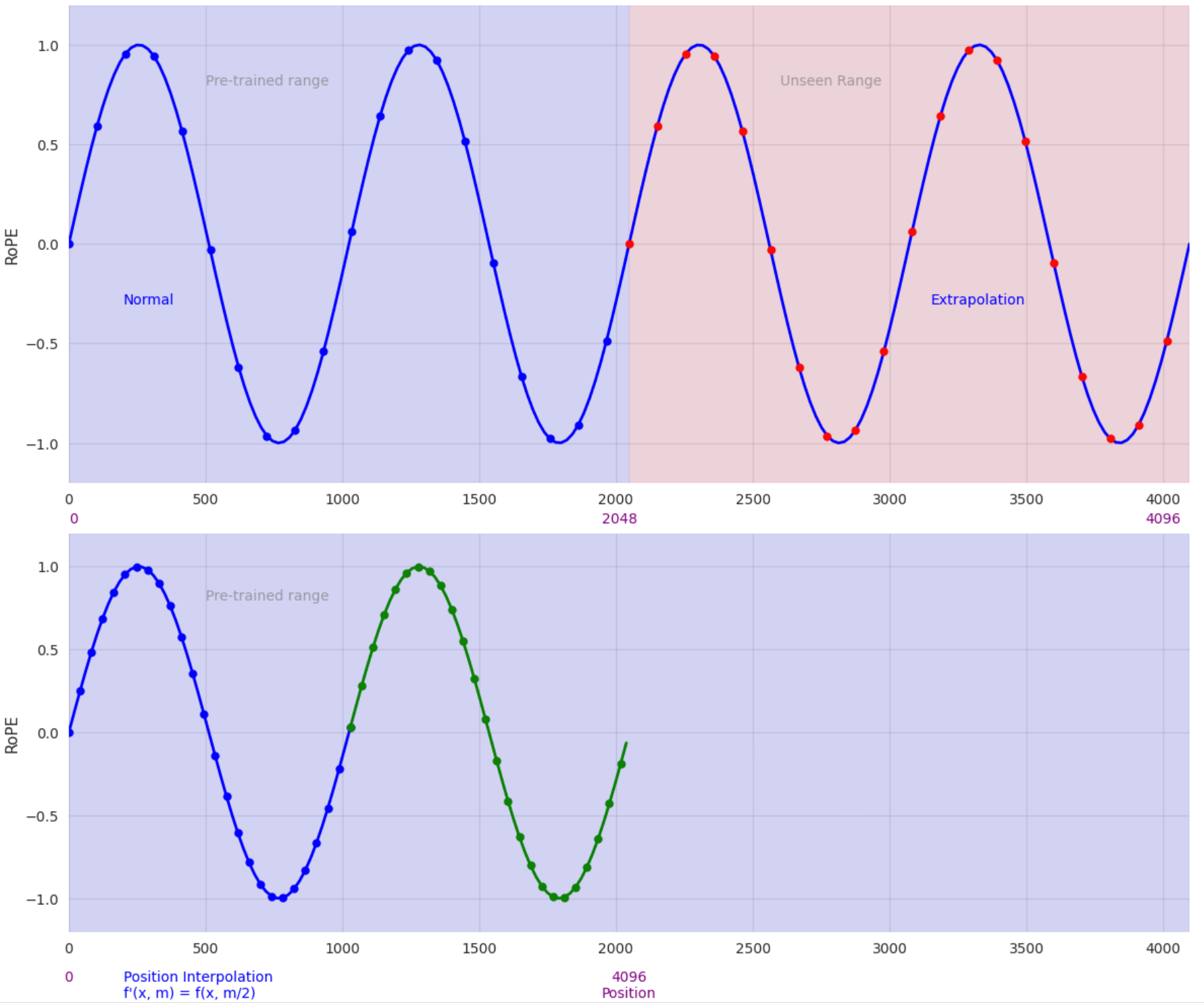

While ALiBi remains the only positional encoding method to demonstrate successful extrapolation to sequence lengths far beyond those encountered during training (Fuller et al. [2023]

To address this challenge, (Chen et al. [2023]

Here $f$ denotes the positional encoding function which takes the context vector $x$ and its position in the sequence $m$.

Thus, they reduce their position indices from \([0, L') \to [0, L)\) to match the original range of indices before computing RoPE. Consequently, as inputs to RoPE, the maximum relative distance between any two tokens is reduced from \(L' \to L\). This alignment of ranges of position indices and relative distances before and after extension helps mitigate the effect on attention score computation due to context window extensions, which make the model easier to adapt.

Recent research on extending the context windows of pre-trained Large Language Models (LLMs) has predominantly focused on position interpolation using RoFormer (Su et al. [2021]

In the domain of computer vision, (Dosovitskiy et al. [2021]

Notably, the method proposed by (Faisal Al-Khateeb et al’s. [2023]

Experimental Evaluation

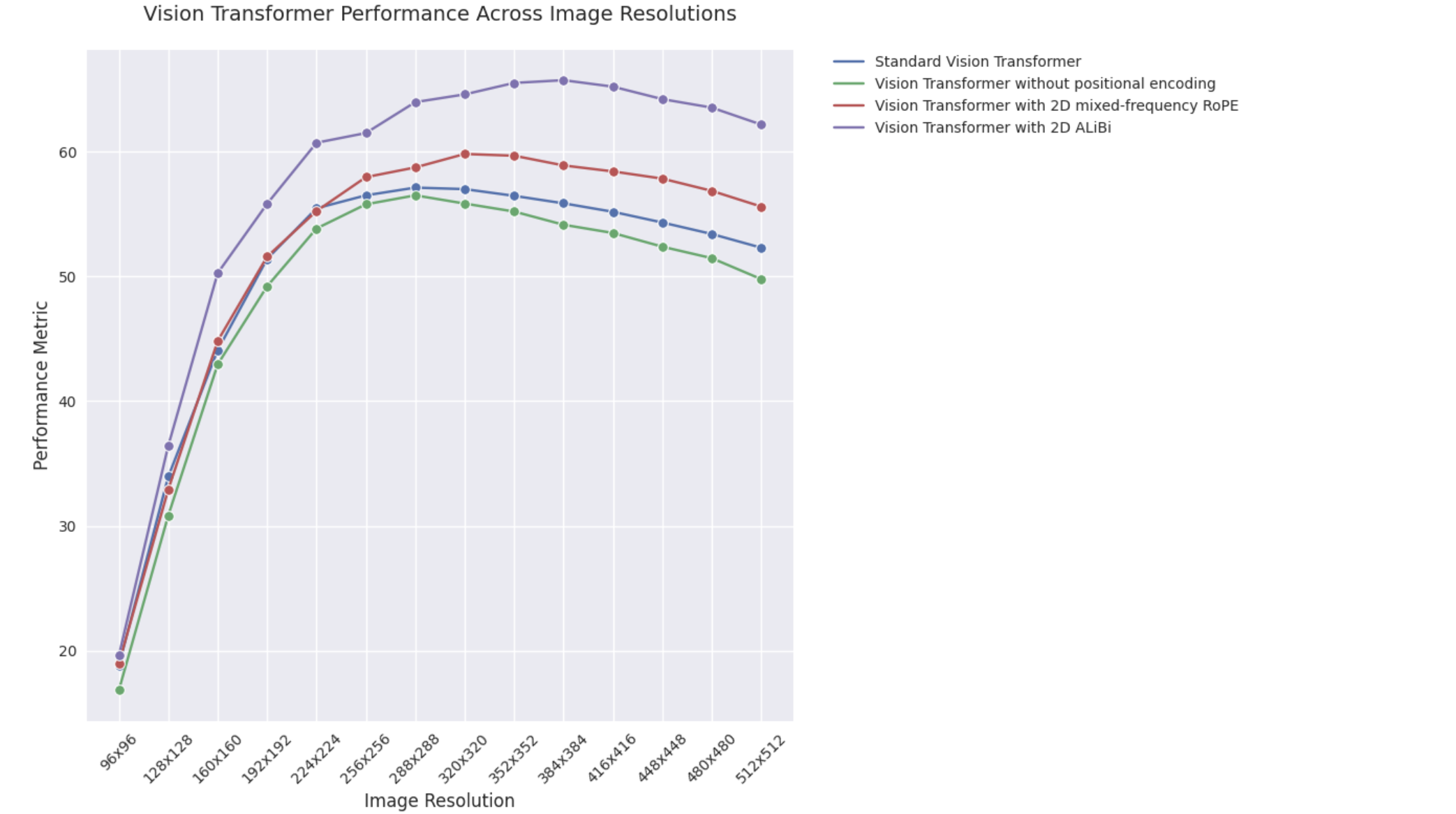

We conducted experiments comparing four architectural variants to empirically verify performance differences :

- Standard Vision Transformer

- Vision Transformer without positional encoding

- Vision Transformer with 2D mixed-frequency RoPE

- Vision Transformer with 2D ALiBi

Experimental Details

We trained all our models using the following hyperparameter scheme and high performance training recipes

| Hyperparameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Dataset | ImageNet100 |

| Training Image Resolution | 224x224 |

| Number of Epochs | 100 |

| Number of Steps | 50K |

| Number of Warmup Steps | 10K |

| Warmup Schedule | Linear |

| Optimizer | AdamW |

| Base Learning Rate | 1e-3 |

| Learning Rate Schedule | Cosine Decay |

| Weight Decay | 0.05 |

| Optimizer Momentum | β1, β2 = 0.9, 0.999 |

| Batch Size | 256 |

| RandAugment | (9, 0.5) |

| Mixup | 0.8 |

| Cutmix | 1.0 |

| Random Erasing | 0.25 |

| Label Smoothing | 0.1 |

Initialisation Scheme:

CLS Token: Initialized using a standard normal distribution with mean 0 and variance 0.02 across all variants. The low variance prevents large initial values, reducing the risk of training instability.

Patch Embedding: We applied LeCun normal initialization for the convolutional patch embedding layer in all variants. Biases are initialized to 0, and weights use a truncated normal distribution based on input features.

Positional Embedding: For the standard Vision Transformer, the learned positional embedding in raster order are initialized with a standard normal distribution mean 0 and variance 0.02.

Classification Head: Both weights and biases in the final classification head are initialized to zero across all variants.

Multi-Head Attention Initialization: Attention layers use a uniform distribution, with bounds determined by the hidden dimension.

MLP Blocks and Layer Norms: Following PyTorch’s default initialization scheme:

- Linear layers use Kaiming uniform initialization.

- Layer normalization has weight initialized to 1 and bias to 0.

Results

| Resolution | Standard Vision Transformer | Vision Transformer without positional encoding | Vision Transformer with 2D mixed-frequency RoPE | Vision Transformer with 2D ALiBi |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 96x96 | 18.80 | 16.82 | 18.98 | 19.60 |

| 128x128 | 33.96 | 30.84 | 32.92 | 36.44 |

| 160x160 | 44.10 | 42.96 | 44.84 | 50.28 |

| 192x192 | 51.42 | 49.22 | 51.60 | 55.84 |

| 224x224 | 55.48 | 53.86 | 55.26 | 60.74 |

| 256x256 | 56.52 | 55.80 | 57.98 | 61.52 |

| 288x288 | 57.14 | 56.52 | 58.76 | 64.00 |

| 320x320 | 57.02 | 55.86 | 59.84 | 64.62 |

| 352x352 | 56.48 | 55.22 | 59.70 | 65.54 |

| 384x384 | 55.88 | 54.16 | 58.92 | 65.76 |

| 416x416 | 55.20 | 53.50 | 58.44 | 65.24 |

| 448x448 | 54.34 | 52.40 | 57.86 | 64.24 |

| 480x480 | 53.42 | 51.48 | 56.88 | 63.56 |

| 512x512 | 52.32 | 49.80 | 55.62 | 62.20 |

Note: Due to limited computational resources, we trained and evaluated our models on ImageNet100

Further, we did not fine-tune the model on a higher sequence length. That is, all our results are for 0 shots. We extrapolated the standard Vision Transformer using 2D interpolation, whereas RoPE and Alibi did not require interpolation techniques as they can handle sequences of variable length. All models were trained using 2 T4 GPUs, with the following training times

| Model | Training Time |

|---|---|

| Standard Vision Transformer | 2 days 7 hours 47 minutes |

| Vision Transformer without positional encoding | 2 days 8 hours 22 minutes |

| Vision Transformer with 2D mixed-frequency RoPE | 2 days 10 hours 45 minutes |

| Vision Transformer with 2D ALiBi | 2 days 8 hours 28 minutes |

Key Findings

- Both ALiBi and RoPE demonstrate superior extrapolation capabilities compared to the baseline ViT.

- ALiBi exhibits better extrapolation performance over RoPE, similar to what has been observed in 1D data.

- ALiBi also offers computational efficiency, reducing training time.

Conclusions

Our analysis of positional encoding mechanisms in Transformer architectures highlights several key insights:

- The evolution of positional encoding and its fundamental role across diverse domains within Transformer architectures.

- The sequence length extrapolation challenge, where RoPE and ALiBi demonstrate particular effectiveness in handling variable sequence lengths, especially ALiBi in extended contexts.

- The adaptation of positional encoding from 1D to 2D tasks, with ALiBi showing practical advantages over RoPE in terms of computational efficiency and implementation simplicity.

- The application of interpolation techniques to enhance the extrapolation capabilities of both RoPE and ALiBi positional encoding methods.

- The empirical validation of RoPE and ALiBi positional encoding in standard Vision Transformers.