An Illustrated Guide to Automatic Sparse Differentiation

In numerous applications of machine learning, Hessians and Jacobians exhibit sparsity, a property that can be leveraged to vastly accelerate their computation. While the usage of automatic differentiation in machine learning is ubiquitous, automatic sparse differentiation (ASD) remains largely unknown. This post introduces ASD, explaining its key components and their roles in the computation of both sparse Jacobians and Hessians. We conclude with a practical demonstration showcasing the performance benefits of ASD.

First-order optimization is ubiquitous in machine learning (ML) but second-order optimization is much less common. The intuitive reason is that high-dimensional vectors (gradients) are cheap, whereas high-dimensional matrices (Hessians) are expensive. Luckily, in numerous applications of ML to science or engineering, Hessians and Jacobians exhibit sparsity: most of their coefficients are known to be zero. Leveraging this sparsity can vastly accelerate automatic differentiation (AD) for Hessians and Jacobians, while decreasing its memory requirements

With this blog post, we aim to shed light on the inner workings of ASD, bridging the gap between the ML and AD communities by presenting well established techniques from the latter field. We start out with a short introduction to traditional AD, covering the computation of Jacobians in both forward and reverse mode. We then dive into the two primary components of ASD: sparsity pattern detection and matrix coloring. Having described the computation of sparse Jacobians, we move on to sparse Hessians.

After discussing applications in machine learning, we conclude with a practical demonstration of ASD, providing performance benchmarks and guidance on when to use ASD over AD.

Automatic differentiation

Let us start by covering the fundamentals of traditional AD. The reader can find more details in the recent book by Blondel and Roulet

AD makes use of the compositional structure of mathematical functions like deep neural networks. To make things simple, we will mainly look at a differentiable function $f$ composed of two differentiable functions $g: \mathbb{R}^{n} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^{p}$ and $h: \mathbb{R}^{p} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^{m}$, such that $f = h \circ g: \mathbb{R}^{n} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^{m}$. The insights gained from this toy example should translate directly to more deeply composed functions $f = g^{(L)} \circ g^{(L-1)} \circ \cdots \circ g^{(1)}$, and even computational graphs with more complex branching.

The chain rule

For a function $f: \mathbb{R}^{n} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^{m}$ and a point of linearization $\mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^{n}$, the Jacobian matrix $J_f(\mathbf{x})$ is the $m \times n$ matrix of first-order partial derivatives, whose $(i,j)$-th entry is

\[\big( \Jf \big)_{i,j} = \dfdx{i}{j} \in \sR \, .\]For a composed function

\[\colorf{f} = \colorh{h} \circ \colorg{g} \, ,\]the multivariate chain rule tells us that we obtain the Jacobian matrix of $f$ by multiplying the Jacobian matrices of $h$ and $g$:

\[\Jfc = \Jhc \cdot \Jgc .\]Figure 1 illustrates this for $n=5$, $m=4$ and $p=3$. We will keep using these dimensions in following illustrations, even though the real benefits of ASD only appear as the dimension grows.

AD is matrix-free

We have seen how the chain rule translates the compositional structure of a function into the product structure of its Jacobian matrix. In practice however, there is a problem: computing intermediate Jacobian matrices is inefficient and often intractable, especially with a dense matrix format. Examples of dense matrix formats include NumPy’s ndarray, PyTorch’s Tensor, JAX’s Array and Julia’s Matrix.

As a motivating example, let us take a look at a tiny convolutional layer. We consider a convolutional filter of size $5 \times 5$, a single input channel and a single output channel. An input of size $28 \times 28 \times 1$ results in a $576$-dimensional output and therefore a $576 \times 784$ Jacobian matrix, the structure of which is shown in Figure 2. All the white coefficients are structural zeros.

If we represent the Jacobian of each convolutional layer as a dense matrix, we waste time computing coefficients which are mostly zero, and we waste memory storing those zero coefficients.

In modern neural network architectures, which can contain over one trillion parameters, computing intermediate Jacobian matrices is not only inefficient: it exceeds available memory.

AD circumvents this limitation by using Jacobian operators that act exactly like Jacobian matrices but without explicitly storing every coefficient in memory. The Jacobian operator $Df: \mathbf{x} \longmapsto Df(\mathbf{x})$ is a linear map which provides the best linear approximation of $f$ around a given point $\mathbf{x}$. Jacobian matrices are the representation of Jacobian operators in the standard basis.

We can now rephrase the chain rule as a composition of operators instead of a product of matrices:

\[\Dfc = \colorf{\D{(h \circ g)}{\vx}} = \Dhc \circ \Dgc \, .\]Note that all terms in this formulation of the chain rule are Jacobian operators. A new visualization for our toy example can be found in Figure 3b. Our illustrations distinguish between matrices and operators by using solid and dashed lines respectively.

Forward-mode AD

Now that we have translated the compositional structure of our function $f$ into a compositional structure of Jacobian operators, we can evaluate them by propagating vectors through them, one subfunction at a time.

Figure 4 illustrates the propagation of a vector $\mathbf{v}_1 \in \mathbb{R}^n$ from the right-hand side. Since we propagate in the order of the original function evaluation ($g$ then $h$), this is called forward-mode AD.

In the first step, we evaluate $Dg(\mathbf{x})(\mathbf{v}_1)$. Since this operation by definition corresponds to

\[\vvc{2} = \Dgc(\vvc{1}) = \Jgc \cdot \vvc{1} \;\in \sR^p \, ,\]it is commonly called a Jacobian-vector product (JVP) or pushforward.

The resulting vector $\mathbf{v}_2$ is then used to compute the subsequent JVP

\[\vvc{3} = \Dhc(\vvc{2}) = \Jhc \cdot \vvc{2} \;\in \sR^m \, ,\]which in accordance with the chain rule is equivalent to

\[\vvc{3} = \Dfc(\vvc{1}) = \Jfc \cdot \vvc{1} \, ,\]the JVP of our composed function $f$.

The computational cost of one JVP of $f$ is approximately the same as the cost of one evaluation of $f$. Note that we did not compute intermediate Jacobian matrices at any point – we only propagated vectors through Jacobian operators.

Reverse-mode AD

We can also propagate vectors through the Jacobian operators from the left-hand side, resulting in reverse-mode AD, shown in Figure 5.

This is commonly called a vector-Jacobian product (VJP) or pullback. Just like forward mode, the cost of one VJP of $f$ is approximately the same as the cost of one evaluation of $f$. However, the memory footprint is larger, as intermediate results of the computation of $f$ must be kept in memory (e.g. hidden activations between layers). Reverse mode is also matrix-free: no intermediate Jacobian matrices are computed at any point.

From Jacobian operators back to Jacobian matrices

In a computationally expensive process we call materialization, we can turn a composition of Jacobian operators into a dense Jacobian matrix. Counterintuitively, this process does not materialize any intermediate Jacobian matrices.

Figure 6 demonstrates how to materialize Jacobian matrices column by column in forward mode. Evaluating the Jacobian operator $Df(\mathbf{x})$ on the $i$-th standard basis vector materializes the $i$-th column of the Jacobian matrix $J_{f}(\mathbf{x})$:

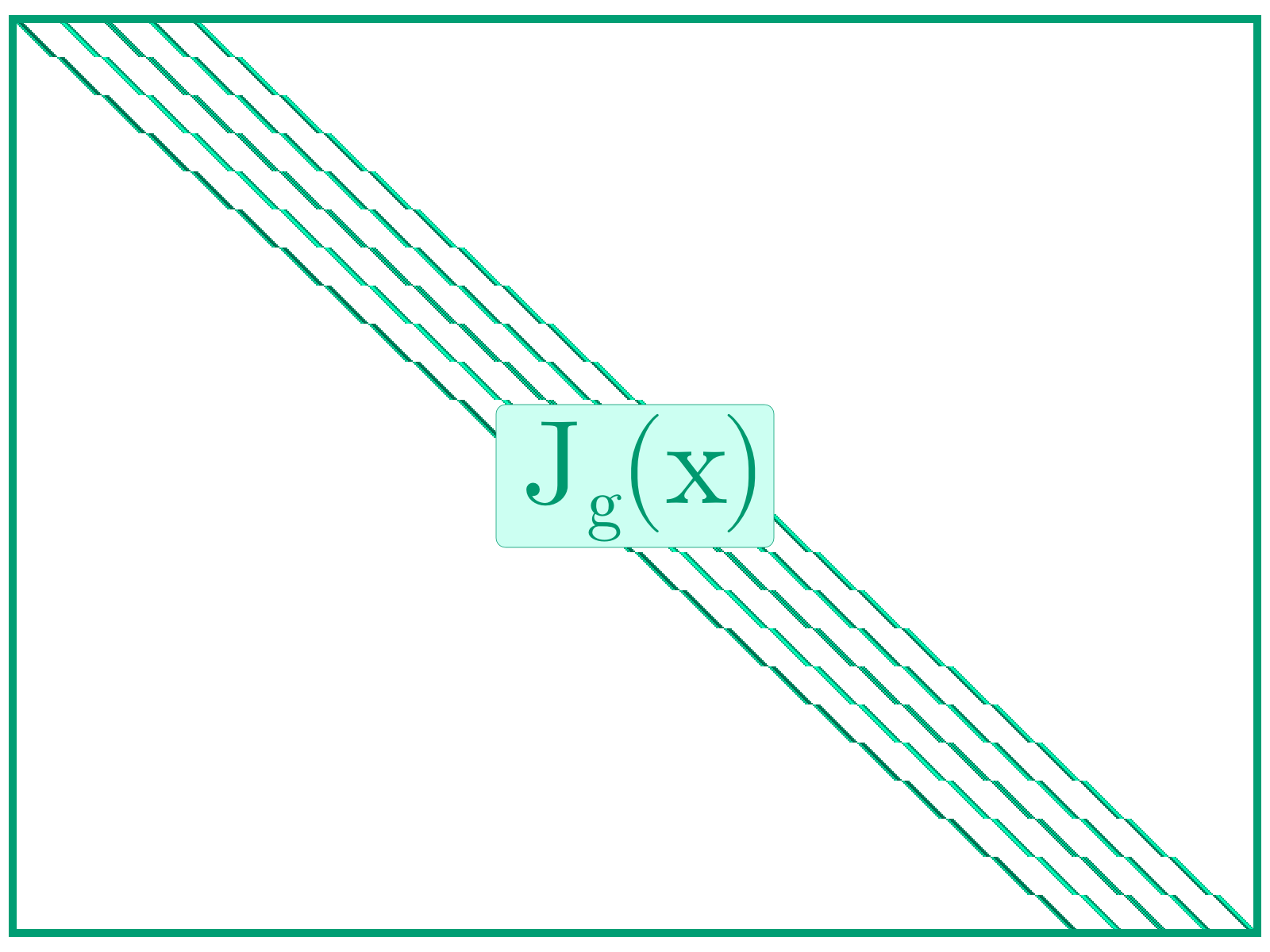

\[\Dfc(\vbc{i}) = \left( \Jfc \right)_\colorv{i,:}\]Thus, recovering the full $m \times n$ Jacobian matrix requires one JVP with each of the $n$ standard basis vectors of the input space. Once again, we distinguish between Jacobian operators and materialized Jacobian matrices by using dashed and solid lines respectively. While we put numbers into the Jacobian operators for illustrative purposes, they are best thought of as black-box functions:

As illustrated in Figure 7, we can also materialize Jacobian matrices row by row in reverse mode. Unlike forward mode in Figure 6, this requires one VJP with each of the $m$ standard basis vectors of the output space.

These processes of materialization are computationally expensive due the fact that each JVP and VJP costs approximately as much as the evaluation of the function $f$ itself.

Automatic sparse differentiation

Sparse matrices

Sparse matrices are matrices in which most elements are zero. As shown in Figure 8, we refer to Jacobian operators as “sparse operators” if they materialize to sparse matrices.

When functions have many inputs and many outputs, a given output does not always depend on every single input. This endows the corresponding Jacobian matrix with a sparsity pattern, where zero coefficients denote an absence of (first-order) dependency. The previous case of a convolutional layer is a simple example. An even simpler example is an activation function applied element-wise, for which the Jacobian matrix is the identity matrix.

Leveraging sparsity

For now, we assume that the sparsity pattern of the Jacobian matrix is always the same, regardless of the input, and that we know it ahead of time. We say that two columns or rows of the Jacobian matrix are structurally orthogonal if, for every index, at most one of them has a nonzero coefficient. In other words, the sparsity patterns of the columns are non-overlapping vectors, whose dot product is always zero regardless of their actual values.

The core idea of ASD is that we can materialize multiple structurally orthogonal columns (or rows) with a single JVP (or VJP). This trick was first suggested in 1974 by Curtis, Powell and Reid

The components of the sum on the right-hand side each correspond to a column of the Jacobian matrix. If these columns are known to be structurally orthogonal, the sum can be uniquely decomposed into its components, a process known as decompression. Thus, a single JVP is enough to retrieve the nonzero coefficients of several columns at once.

This specific example using JVPs corresponds to forward-mode ASD and is visualized in Figure 9, where all structurally orthogonal columns have been colored in matching hues. By computing a single JVP with the vector $\mathbf{e}_1 + \mathbf{e}_2 + \mathbf{e}_5$, we obtain the sum of the first, second and fifth column of our Jacobian matrix.

A second JVP with the vector $\mathbf{e}_3 + \mathbf{e}_4$ gives us the sum of the remaining columns. We then assign the values in the resulting vectors back to the appropriate entries of the Jacobian matrix. This final decompression step is shown in Figure 10.

The same idea can also be applied to reverse-mode AD, as shown in Figure 11. Instead of leveraging orthogonal columns, we rely on orthogonal rows. We can then materialize multiple rows in a single VJP.

Pattern detection and coloring

Unfortunately, our initial assumption had a major flaw. Since AD only gives us a composition of Jacobian operators, which are black-box functions, the structure of the corresponding Jacobian matrix is completely unknown. In other words, we cannot tell which rows and columns form structurally orthogonal groups without first materializing a Jacobian matrix. But if we materialize this matrix via traditional AD, then ASD isn’t necessary anymore.

The solution to this problem is shown in Figure 12 (a): in order to find structurally orthogonal columns (or rows), we don’t need to materialize the full Jacobian matrix. Instead, it is enough to detect the sparsity pattern of the matrix. This binary-valued pattern contains enough information to deduce structural orthogonality. From there, we use a coloring algorithm to group orthogonal columns (or rows) together. Such a coloring can be visualized on Figure 12 (b), where the yellow columns will be evaluated together (first JVP) and the light blue ones will be evaluated together (second JVP), for a total of 2 JVPs instead of 5.

To sum up, ASD consists of four steps:

- Pattern detection

- Coloring

- Compressed AD

- Decompression

This compression-based pipeline is described at length by Gebremedhin, Manne and Pothen

We now discuss the first two steps in more detail. These steps can be much slower than a single call to the function $f$, but they are usually much faster than a full computation of the Jacobian with AD. This makes the sparse procedure worth it even for moderately large matrices. Additionally, if we need to compute Jacobians multiple times (for different inputs) and are able to reuse the sparsity pattern and the coloring result, the cost of this prelude can be amortized over several subsequent evaluations.

Pattern detection

Mirroring the diversity of AD systems, there are also many possible approaches to sparsity pattern detection, each with its own advantages and tradeoffs. The work of Dixon

The method we present corresponds to a binary version of a forward-mode AD system, similar in spirit to

Index sets

Our goal with sparsity pattern detection is to quickly compute the binary pattern of the Jacobian matrix. One way to achieve better performance than traditional AD is to encode row sparsity patterns as index sets. The $i$-th row of the Jacobian is given by

\[\big( \Jf \big)_{i,:} = \left[\dfdx{i}{j}\right]_{1 \le j \le n} = \begin{bmatrix} \dfdx{i}{1} & \ldots & \dfdx{i}{n} \end{bmatrix} \, .\]However, since we are only interested in the binary pattern

\[\left[\dfdx{i}{j} \neq 0\right]_{1 \le j \le n} \, ,\]we can instead represent the sparsity pattern of the $i$-th row of a Jacobian matrix by the corresponding index set of non-zero values

\[\left\{j \;\Bigg|\; \dfdx{i}{j} \neq 0\right\} \, .\]These equivalent sparsity pattern representations are illustrated in Figure 13. Each row index set tells us which inputs influenced a given output, at the first-order. For instance, output $i=2$ was influenced by inputs $j=4$ and $j=5$.

Efficient propagation

Figure 14 shows the traditional forward mode pass we want to avoid: propagating a full identity matrix through a Jacobian operator would not only materialize the Jacobian matrix of $f$, but also all intermediate Jacobian matrices. As previously discussed, this is not a viable option due to its inefficiency and high memory requirements.

Instead, we initialize an input vector with index sets corresponding to the identity matrix. An alternative view on this vector is that it corresponds to the index set representation of the Jacobian matrix of the input, since $\frac{\partial x_i}{\partial x_j} \neq 0$ only holds for $i=j$.

Our goal is to propagate this index set such that we get an output vector of index sets that corresponds to the Jacobian sparsity pattern. This idea is visualized in Figure 15.

Abstract interpretation

Instead of going into implementation details, we want to provide some intuition on the second key ingredient of this typical forward-mode sparsity detection system: abstract interpretation.

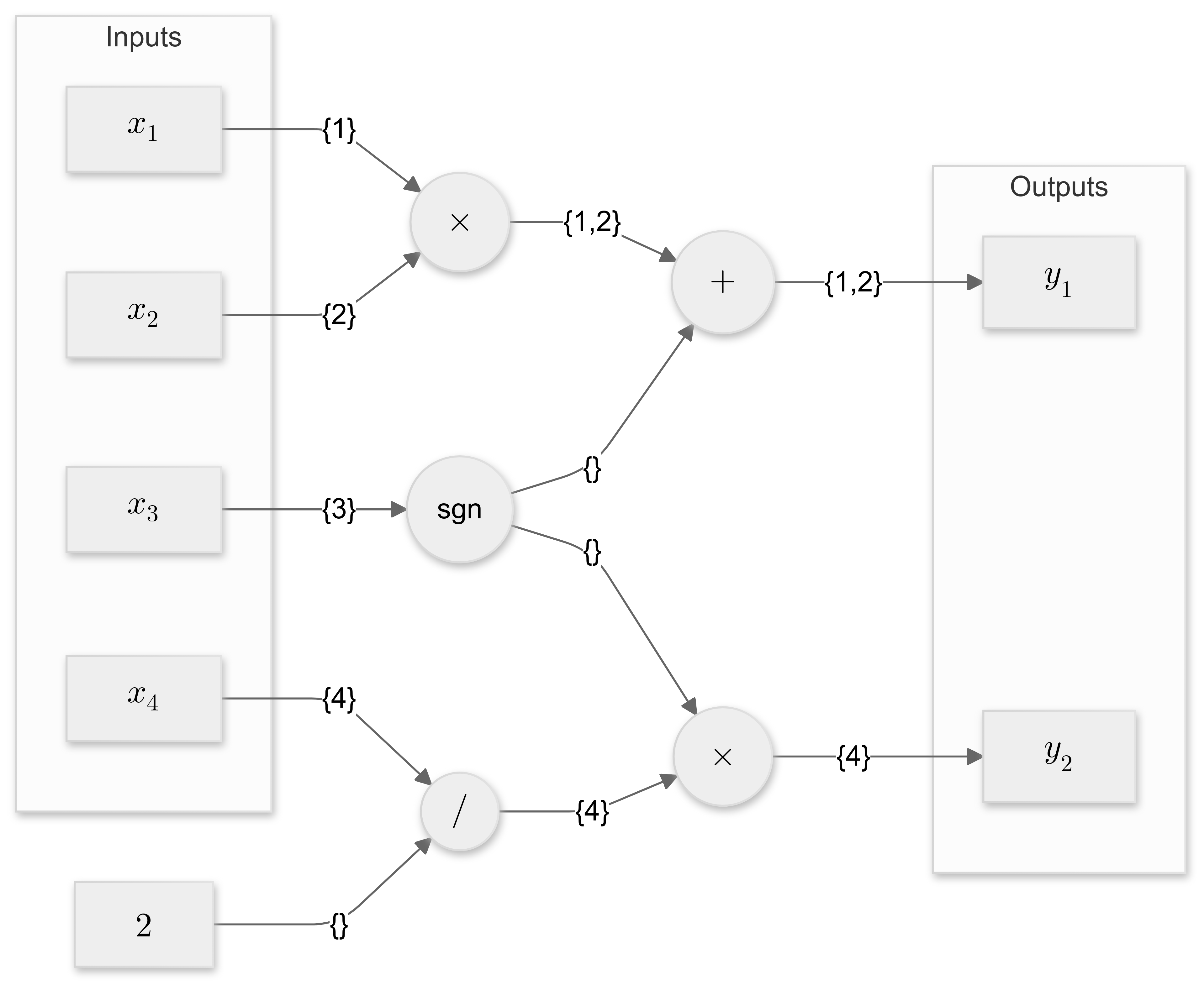

We will demonstrate this on a second toy example, the function

\[f(\vx) = \begin{bmatrix} x_1 x_2 + \text{sgn}(x_3)\\ \text{sgn}(x_3) \frac{x_4}{2} \end{bmatrix} \, .\]The corresponding computational graph is shown in Figure 16, where circular nodes correspond to primitive functions, in this case addition, multiplication, division and the sign function. Scalar inputs $x_i$ and outputs $y_j$ are shown in rectangular nodes. Instead of evaluating the original compute graph for a given input $\mathbf{x}$, all inputs are seeded with their respective input index sets. Figure 16 annotates these index sets on the edges of the computational graph.

Abstract interpretation means that we imbue the computational graph with a different meaning. Instead of computing its output value, each primitive function must accumulate the index sets of its inputs, then propagate these index sets to the output, but only if the corresponding derivative is non-zero anywhere in the input domain.

Since addition, multiplication and division globally have non-zero derivatives with respect to both of their inputs, the index sets of their inputs are accumulated and propagated. The sign function has a zero derivative for any input value. It therefore doesn’t propagate the index set of its input and instead returns an empty set.

Figure 16 shows the resulting output index sets $\{1, 2\}$ and $\{4\}$ for outputs 1 and 2 respectively. These match the analytic Jacobian matrix

\[J_f(\mathbf{x}) = \begin{bmatrix} x_2 & x_1 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & \frac{\text{sgn}(x_3)}{2} \end{bmatrix} \, .\]Local and global patterns

The type of abstract interpretation shown above corresponds to global sparsity detection, computing index sets

\[\left\{j \;\Bigg|\; \dfdx{i}{j} \neq 0 \, \text{for some} \, \mathbf{x} \in \sR^{n} \right\}\]that are valid over the entire input domain. Another type of abstract interpretation can be implemented, in which the original primal computation is propagated alongside index sets, computing

\[\left\{j \;\Bigg|\; \dfdx{i}{j} \neq 0 \right\}\]for a specific input $\mathbf{x}$. These local sparsity patterns are strict subsets of global sparsity patterns, and can therefore result in fewer colors. However, they need to be recomputed when changing the input.

Coloring

Once we have detected a sparsity pattern, our next goal is to decide how to group the columns (or rows) of the Jacobian matrix. The columns (or rows) in each group will be evaluated simultaneously using a single JVP (or VJP), with a linear combination of basis vectors called a seed. If the members of the group are structurally orthogonal, then this gives all the necessary information to retrieve every nonzero coefficient of the matrix.

Graph formulation

Luckily, this grouping problem can be reformulated as graph coloring, which is very well studied. Let us build a graph $\mathcal{G} = (\mathcal{V}, \mathcal{E})$ with vertex set $\mathcal{V}$ and edge set $\mathcal{E}$, such that each column is a vertex of the graph, and two vertices are connected if and only if their respective columns share a non-zero index. Put differently, an edge between vertices $j_1$ and $j_2$ means that columns $j_1$ and $j_2$ are not structurally orthogonal. Note that there are more efficient graph representations, summed up in

We want to assign to each vertex $j$ a color $c(j)$, such that any two adjacent vertices $(j_1, j_2) \in \mathcal{E}$ have different colors $c(j_1) \neq c(j_2)$. This constraint ensures that columns in the same color group are indeed structurally orthogonal. If we can find a coloring which uses the smallest possible number of distinct colors, it will minimize the number of groups, and thus the computational cost of the AD step.

Figure 17 shows an optimal coloring using two colors, whereas Figure 18 uses a suboptimal third color, requiring an extra JVP to materialize the Jacobian and therefore increasing the computational cost of ASD. Figure 19 shows an infeasible coloring: vertices 2 and 4 on the graph are adjacent, but share a color. This results in overlapping columns.

If we perform column coloring, forward-mode AD is required, while reverse-mode AD is needed for row coloring.

Greedy algorithm

Unfortunately, the graph coloring problem is NP-hard: there is currently no way to solve it in polynomial time for every instance. The optimal solution is known only for specific patterns, such as banded matrices. However, efficient heuristics exist which generate good enough solutions in reasonable time. The most widely used heuristic is the greedy algorithm, which processes vertices one after the other. This algorithm assigns to each vertex the smallest color that is not already present among its neighbors, and it never backtracks. A crucial hyperparameter is the choice of ordering, for which various criteria have been proposed

Bicoloring

A more advanced coloring technique called bicoloring allows combining forward and reverse modes, because the recovery of the Jacobian matrix leverages both columns (JVPs) and rows (VJPs)

Figure 20 shows bicoloring on a toy example in which no pair of columns or rows is structurally orthogonal. Even with ASD, materializing the Jacobian matrix would require $5$ JVPs in forward-mode or $4$ VJPs in reverse mode. However, if we use both modes simultaneously, we can materialize the full Jacobian matrix by computing only $1$ JVP and $1$ VJP.

Second order

While first-order automatic differentiation AD focuses on computing the gradient or Jacobian matrix, second-order AD extends the same ideas to the Hessian matrix

\[\nabla^2 f (\mathbf{x}) = \left(\frac{\partial^2 f(\mathbf{x})}{\partial x_i ~ \partial x_j} \right)_{i,j} \, .\]The Hessian contains second-order partial derivatives of a scalar function, essentially capturing the curvature of the function at a point. This is particularly relevant in optimization, where the Hessian provides crucial information about the function’s local behavior. Specifically, the Hessian allows us to distinguish between local minima, maxima, and saddle points. By incorporating second-order information, optimization algorithms converge more robustly where the gradient alone doesn’t provide enough information for effective search directions.

Hessian-vector products

For second-order AD, the key subroutine is the Hessian-vector product (HVP). The Hessian is the Jacobian matrix of the gradient function $\nabla f: \mathbf{x} \mapsto \nabla f(\mathbf{x})$, that is,

\[\nabla^2 f (\mathbf{x}) = J_{\nabla f}(\mathbf{x}) \, .\]An HVP computes the product of the Hessian matrix with a vector, which can be viewed as the JVP of the gradient function.

\[\nabla^2 f(\mathbf{x}) \cdot \mathbf{v} = D[\nabla f](\mathbf{x})(\mathbf{v})\]Note that the gradient function is itself computed via a VJP of $f$. Thus, the HVP approach we described computes the JVP of a VJP, giving it the name “forward over reverse”. In forward-over-reverse HVPs, the complexity of a single product scales roughly with the complexity of the function $f$ itself. This procedure was first considered by Pearlmutter

The Hessian has a symmetric structure (equal to its transpose), which means that matrix-vector products and vector-matrix products coincide. This explains why we don’t need a VHP in addition to the HVP. This specificity can be exploited in the sparsity detection as well as in the coloring phase.

Second order pattern detection

Detecting the sparsity pattern of the Hessian is more complicated than for the Jacobian. This is because, in addition to the usual linear dependencies, we now have to account for nonlinear interactions in the computational graph. The operator overloading method of Walther

For instance, if $f(\mathbf{x})$ involves a term of the form $x_1 + x_2$, it will not directly affect the Hessian. However, we cannot ignore this term, since multiplying it with $x_3$ to obtain an output $f(\mathbf{x}) = (x_1 + x_2)\,x_3$ will yield non-zero coefficients at positions $(1, 3)$, $(3, 1)$, $(2, 3)$ and $(3, 2)$. Thus, the abstract interpretation system used for second-order pattern detection needs a finer classification of primitive functions. It must distinguish between locally constant, locally linear, and locally nonlinear behavior in each argument, and distinguish between zero and non-zero cross-derivatives.

Symmetric coloring

When it comes to graph coloring for the Hessian, there are more options for decompression thanks to symmetry. Even if two columns in the Hessian are not structurally orthogonal, missing coefficients can be recovered by leveraging the corresponding rows instead of relying solely on the columns. In other words, if $H_{ij}$ is lost during compression because of colliding nonzero coefficients, there is still a chance to retrieve it through $H_{ji}$. This backup storage enables the use of fewer distinct colors, reducing the complexity of the AD part compared to traditional row or column coloring.

Powell and Toint

Applications

ASD is useful in applications which involve the computation of full Jacobian or Hessian matrices with sparsity. Let us discuss one of the examples given in the 2024 ICLR blog post How to compute Hessian-vector products?

However, when it is possible to materialize the whole Hessian matrix, direct linear solvers can be used (e.g. based on matrix factorization). As we have seen, ASD unlocks this option whenever the Hessian matrix is sparse enough. In terms of performance, computing a sparse Hessian matrix might require fewer HVPs overall than applying an iterative solver like the conjugate gradient method. The exact performance depends on the number of colors in the sparsity pattern of the Hessian, as well as the numerical precision expected from the iterative solver (which influences the number of iterations, hence the number of HVPs). In terms of numerical accuracy, direct solvers are more robust than their iterative counterparts. Finally, in terms of compatibility, some prominent nonlinear optimization libraries only support Hessian matrices, and not Hessian operators.

The same reasoning also applies to Jacobian matrices, which can appear in settings like Newton’s method for root-finding, implicit differentiation

Demonstration

We complement this tutorial with a demonstration of automatic sparse differentiation in a high-level programming language, namely the Julia language

Necessary packages

Here are the packages we will use for this demonstration.

- SparseConnectivityTracer.jl

: Sparsity pattern detection with operator overloading. - SparseMatrixColorings.jl

: Greedy algorithms for colorings, decompression utilities. - ForwardDiff.jl

: Forward-mode AD and computation of JVPs. - DifferentiationInterface.jl

: High-level interface bringing all of these together, originally inspired by .

This modular pipeline comes as a replacement and extension of a previous ASD system in Julia

Like in any other language, the first step is importing the dependencies:

using DifferentiationInterface, DifferentiationInterfaceTest

using SparseConnectivityTracer, SparseMatrixColorings

import ForwardDiff

The syntax we showcase is accurate as of the following package versions:

[a0c0ee7d] DifferentiationInterface v0.6.48

[a82114a7] DifferentiationInterfaceTest v0.9.5

[f6369f11] ForwardDiff v0.10.38

[9f842d2f] SparseConnectivityTracer v0.6.15

[0a514795] SparseMatrixColorings v0.4.14

Test function

As our test function, we choose a very simple iterated difference operator. It takes a vector $\mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^n$ and outputs a slightly shorter vector $y \in \mathbb{R}^{n-k}$ depending on the number of iterations $k$. In pure Julia, this is written as follows (using the built-in diff recursively):

function iter_diff(x, k)

if k == 0

return x

else

y = iter_diff(x, k - 1)

return diff(y)

end

end

Let us check that the function returns what we expect:

julia> iter_diff([1, 4, 9, 16], 1)

3-element Vector{Int64}:

3

5

7

julia> iter_diff([1, 4, 9, 16], 2)

2-element Vector{Int64}:

2

2

Backend switch

The key concept behind DifferentiationInterface.jl is that of backends. There are several AD systems in Julia, each with different features and tradeoff, that can be accessed through a common API. Here, we use ForwardDiff.jl as our AD backend:

ad = AutoForwardDiff()

To build an ASD backend, we bring together three ingredients corresponding to each step:

sparsity_detector = TracerSparsityDetector() # from SparseConnectivityTracer

coloring_algorithm = GreedyColoringAlgorithm() # from SparseMatrixColorings

asd = AutoSparse(ad; sparsity_detector, coloring_algorithm)

Jacobian computation

We can now compute the Jacobian of iter_diff (with respect to $\mathbf{x}$) using either backend, and compare the results. Just like AD, ASD is fully automatic. It doesn’t require the user to change any code besides specifying a backend:

julia> x, k = rand(10), 3;

julia> jacobian(iter_diff, ad, x, Constant(k))

7×10 Matrix{Float64}:

-1.0 3.0 -3.0 1.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

0.0 -1.0 3.0 -3.0 1.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

0.0 0.0 -1.0 3.0 -3.0 1.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

0.0 0.0 0.0 -1.0 3.0 -3.0 1.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 -1.0 3.0 -3.0 1.0 0.0 0.0

0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 -1.0 3.0 -3.0 1.0 0.0

0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 -1.0 3.0 -3.0 1.0

julia> jacobian(iter_diff, asd, x, Constant(k))

7×10 SparseArrays.SparseMatrixCSC{Float64, Int64} with 28 stored entries:

-1.0 3.0 -3.0 1.0 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅

⋅ -1.0 3.0 -3.0 1.0 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅

⋅ ⋅ -1.0 3.0 -3.0 1.0 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅

⋅ ⋅ ⋅ -1.0 3.0 -3.0 1.0 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅

⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ -1.0 3.0 -3.0 1.0 ⋅ ⋅

⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ -1.0 3.0 -3.0 1.0 ⋅

⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ -1.0 3.0 -3.0 1.0

In one case, we get a dense matrix, in the other it is sparse. Note that in Julia, linear algebra operations are optimized for sparse matrices, which means this format can be beneficial for downstream use. We now show that sparsity also unlocks faster computation of the Jacobian itself.

Preparation

Sparsity pattern detection and matrix coloring are performed in a so-called “preparation step”, whose output can be reused across several calls to jacobian (as long as the pattern stays the same).

Thus, to extract more performance, we can create this object only once

prep = prepare_jacobian(iter_diff, asd, x, Constant(k))

and then reuse it as much as possible, for instance inside the loop of an iterative algorithm (note the additional prep argument):

jacobian(iter_diff, prep, asd, x, Constant(k))

Inside the preparation result, we find the output of sparsity pattern detection

julia> sparsity_pattern(prep)

7×10 SparseArrays.SparseMatrixCSC{Bool, Int64} with 28 stored entries:

1 1 1 1 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅

⋅ 1 1 1 1 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅

⋅ ⋅ 1 1 1 1 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅

⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 1 1 1 1 ⋅ ⋅ ⋅

⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 1 1 1 1 ⋅ ⋅

⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 1 1 1 1 ⋅

⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ 1 1 1 1

and the coloring of the columns:

julia> column_colors(prep)

10-element Vector{Int64}:

1

2

3

4

1

2

3

4

1

2

Note that it uses only $c = 4$ different colors, which means we need $4$ JVPs instead of the initial $n = 10$ to reconstruct the Jacobian.

julia> ncolors(prep)

4

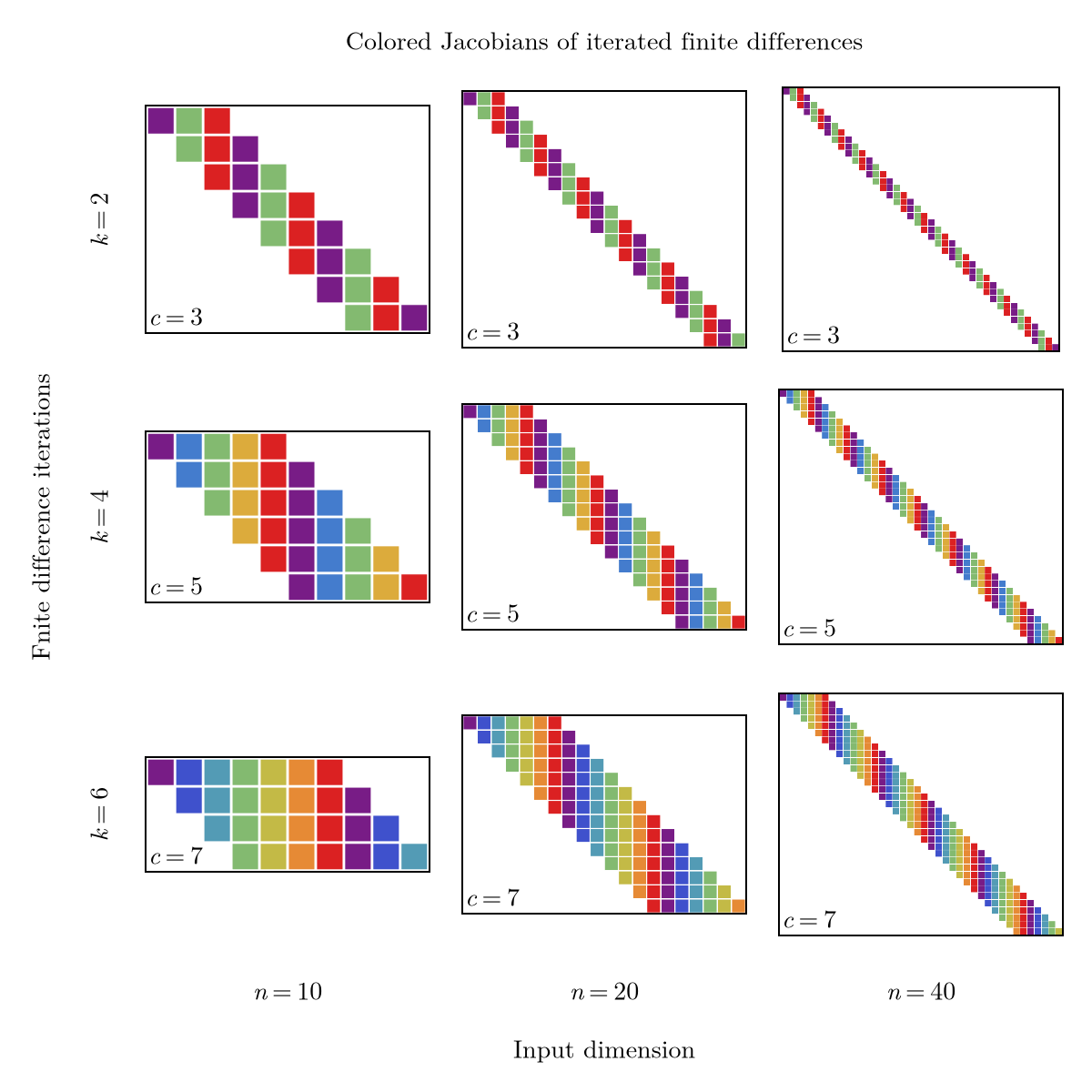

Coloring visualization

We just saw that there is a discrepancy between the number of different colors $c$ and the input size $n$. This ratio $n / c$ typically gets larger as the input grows, which makes sparse differentiation more and more competitive.

We illustrate this with the Jacobians of iter_diff for several values of $n$ and $k$:

The main takeaway of Figure 21 is that in this case, the number of colors does not depend on the dimension $n$, only on the number of iterations $k$. In fact, iter_diff with $k$ iterations gives rise to a banded Jacobian with $k+1$ bands, for which we can easily verify that the optimal coloring uses as many colors as bands, i.e. $c = k+1$. For this particular case, the greedy coloring also happens to find the optimal solution.

Performance benefits

Here we present a benchmark for the Jacobian of iter_diff with varying $n$ and fixed $k$. Our goal is to find out when sparse differentiation becomes relevant. Benchmark data can be generated with the following code:

scenarios = [

Scenario{:jacobian, :out}(iter_diff, rand(n); contexts=(Constant(k),))

for n in round.(Int, 10 .^ (1:0.3:4))

]

data = benchmark_differentiation(

[ad, asd], scenarios; benchmark=:full, logging=true

)

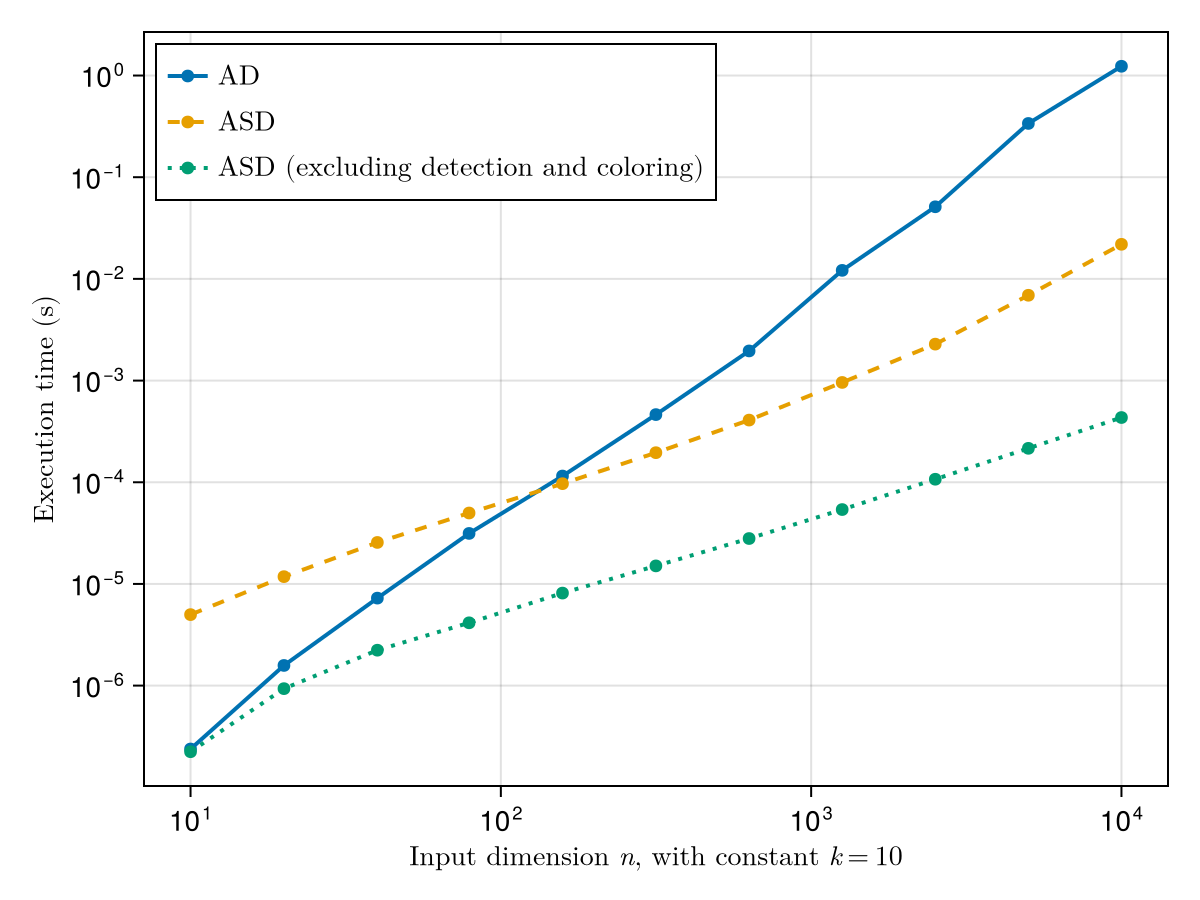

It gives rise to the following performance curves (lower is better):

As we can see on Figure 22, there are three main regimes:

- For very small inputs, we gain nothing by leveraging sparsity.

- For medium-sized inputs, sparsity handling is only useful if we can amortize the cost of detection and coloring.

- For very large inputs, even the overhead of detection and coloring is worth paying as part of a sparse Jacobian computation.

Importantly, ASD can yield an asymptotic speedup compared to AD, not just a constant one. In our test case, the cost of a JVP for iter_diff scales with $kn$. Sparse differentiation requires $c$ JVPs instead of $n$, so with $c = k+1$ here its total cost scales as $\Theta(k^2 n)$ instead of $\Theta(k n^2)$. Thus, on the log-log plot of Figure 22, the ASD curve (without detection) has a slope of $1$ while the AD curve has a slope of $2$.

Although the specific thresholds between regimes are problem-dependent, our conclusions hold in general.

Conclusion

By now, the reader should have a better understanding of how sparsity can be used for efficient differentiation.

But should it always be used? Here are a list of criteria to consider when choosing between AD and ASD:

- Which derivative is needed? When computing gradients of scalar functions using reverse mode, sparsity can’t be leveraged, as only a single VJP is required. In practice, ASD only speeds up derivatives like the Jacobian and Hessian which have a matrix form.

- What operations will be performed on the derivative matrix? For a single matrix-vector product $J \mathbf{v}$, the Jacobian operator will always be faster. But if we want to solve linear systems $J \mathbf{v} = \mathbf{y}$, then it may be useful to compute the full Jacobian matrix first to leverage sparse factorization routines.

- How expensive is the function at hand? This directly impacts the cost of a JVP, VJP or HVP, which scales with the cost of one function evaluation.

- How sparse would the matrix be? This dictates the efficiency of sparsity detection and coloring, as well as the number of matrix-vector products necessary. While it may be hard to get an exact estimate, concepts like partial separability can help provide upper bounds

. In general, the relation between the number of colors $c$ and the dimension $n$ is among the most crucial quantities to analyze.

In simple settings (like finite differences, which create banded Jacobians), the sparsity pattern and optimal coloring can be derived manually. But as soon as the function becomes more complex, automating this process becomes essential to ensure wide usability. We hope that the exposition above will motivate the implementation of user-friendly ASD in a variety of programming languages and AD frameworks.